1. Personal Processing

Personal processing is about taking time to connect with ourselves – to reflect on who we are, how we act, and how we relate to others and the world around us. Using a range of activities, this module seeks to provide opportunities to better understand ourselves by thinking about our identity, our relationship to society, our learnt biases, and our needs.

- Overview

- Deep Reflection: Understanding Ourselves and Understanding Others

- What Happens In Our Brain When Our Views Are Challenged?

- Power & Privilege

- Reflecting on Identity Privilege

- Personal Visioning

- Building Courage

- Understanding Emotions

- Active Listening

Overview

Why Personal Processing?

Before working to transform our local communities and connecting with others, we think it is really important to start with ourselves. We are all shaped by our experiences, by the society in which we live and by our identity, the features of which we may choose for ourselves or have placed upon us by society. We, subsequently, engage with the world in a way that is unique and specific to us: objectivity does not exist. The more time we, therefore, take for reflection and for understanding ourselves and the complexity of our stories and identities, the more we will understand and empathise with others.

This process of turning the dialogue inwards will also provide opportunities for us to examine and challenge our biases. Only by critically questioning why we think what we do and why we act how we do, will we be able to hold ourselves to account when we make judgements on others. Such critical reflection can transform the way that we communicate with everyone, particularly those who we regard as different.

Moreover, taking time to understand ourselves will enable us to consider and respond to our feelings and needs. Sometimes it is difficult to listen to ourselves and to acknowledge our needs, but it is vital if we are going to create a sustainable society based on compassion - we need to look after ourselves to avoid burnout and to be able to care for others.

By engaging in personal processing, we can strengthen our ability to build genuine connections with the people we encounter, can make space for ourselves and our needs, and can ultimately grow as people.

Useful Link:

Deep Reflection: Understanding Ourselves and Understanding Others

The activities outlined below have all been selected to help initiate a process of self-reflection and understanding.These activities have been adapted from teaching resources created by the educational charity, Facing History and Ourselves. They have been placed in a suggested order, though it is down to each individual to design their journey of self-discovery.

- Reflect on Identity and Values

- Consider Single Stories and Stereotypes

- Acknowledge and Challenge Assumptions

To transform our communities, we must engage with others, but first we must engage with ourselves.

Reflect on Identity and Values

The activities in this section are adapted from the following Facing History and Ourselves’ resources: Teaching Strategy: Identity Charts.

Before we enter into dialogue with others we should be asking ourselves: “Who am I? How does my identity impact my ability to communicate with and listen to others?”. The following activities will help create a foundation for such reflection.

- On a piece of paper, note down a response to the question, Who am I? You might choose to list words or phrases that you, or others, might use to describe yourself.

- Create an Identity Chart.

Draw a circle in the middle of a page and write your name in it. Then draw arrows pointing out from the circle and note down the combination of things that make you who you are (like a mindmap or a brainstorm, see an example here).

Use the following list to assist you, if desired:

- Role in Family

- Profession / Skills

- Hobbies / Interests

- Personality

- Background / Upbringing

- Heritage / Nationality

- Colour you have been racialised as

- Physical Characteristics

- Beliefs / Religion

- Gender

-

If applicable, identify features on your identity chart that:

- You have felt proud of

- You have felt ashamed of

- Others find surprising

- Are central to who you are

- Are labels that others have put upon you

- Have changed over time

-

Consider the following questions:

Some aspects of our identities change over our lifetimes as we grow up and get new skills or new interests.

- What does this tell us about the concept of identity?

- Why is it important to keep this in mind when we are interacting with others?

Some aspects of our identity feel very central to who we are.

- Why is it important to be aware of this when interacting with others?

- What is the relationship between aspects of your identity and your values?

Some aspects of our identity are labels that others put upon us, but which we do not agree with.

- What labels have others put on you? How have they made you feel?

- Why do you think people put labels on others?

- What are the consequences of such labelling?

Consider “Single Stories” and Stereotypes

The activities in this section are adapted from the following Facing History and Ourselves’ resource: The Danger of a Single Story.

- Watch Chimamanda Adichie’s TED Talk The Danger of a Single Story

- Create an identity chart for Chimamanda Adichie.

- Which labels on the chart represent how she sees her own identity?

- Which ones represent how some others view her?

- Consider the following questions:

-

What does Adichie mean by a “single story”?

- What examples does she give?

- Why does she believe “single stories” are dangerous?

- What does she say the relationship between “single stories” and stereotypes is?

-

Is there a single story that others often use to define you?

- What is this single story?

- What impact does it have / has it had on you?

-

Can you think of other examples of “single stories” that may be part of your own worldview?

- Where do those “single stories” come from?

- How can we find a “balance of stories”?

Acknowledge and Challenge Assumptions

The activities in this section are adapted from the following Facing History and Ourselves’ resource: Challenging Assumptions with Curiosity.

- Respond to the following questions:

-

Based on your identity, what assumptions do you think people might make about you?

-

What questions could someone who holds such assumptions about you ask you to better understand your values and perspective?

-

If applicable, think about one assumption that someone has made about you

- What was this assumption?

- How did this assumption make you feel?

- What were the consequences of this assumption being made?

-

If applicable, think about one assumption you have made about someone else?

- What was this assumption?

- What prompted you to make it?

- What were the consequences of making this assumption?

- Watch this video on how the night unfolded as the UK left the EU, which has interviews with people who hold different beliefs and opinions about Brexit. Then respond to the following questions:

-

About which person in the video do you have the most positive assumptions?

- What about them do you think creates these positive assumptions? (Consider race, gender, clothing, style of talking, accent, opinions, and other factors.)

- What questions might you ask this person to better understand their values and perspective?

-

About which person in the video do you have the most negative assumptions?

- What about them do you think creates these negative assumptions? (Consider race, gender, clothing, style of talking, accent, opinions, and other factors.)

- What questions might you ask this person to better understand their values and perspective?

-

Sit in a public place for at least 30 minutes and observe the people around you. Notice the assumptions you make. Record these assumptions and what you think led you to make them. (The person’s clothing? Their age? Their gender? Their body language?) Then, record questions you’d like to ask this person to better inform your perception of them.

COVID-19 adaptation: If you are in quarantine or isolation, consider the assumptions you make about people you speak to, read about or watch on TV throughout the day.

What Happens In Our Brain When Our Views Are Challenged?

Everyone has had a conversation with someone who shares distinctly different views and has left it feeling frustrated, as if there has been breakdown in communication and there is nothing we can do to make the other person understand our perspective. This conflict is more likely to appear when the discussions centre on topics that we really care about, and that we view as connected to our identity.

To help temper future conflict around the communication of strongly held opinions and beliefs, it is important to understand what is going on in our brain:

- Until adolescence, our brain works like a flexible sponge, absorbing information in our external environment to better understand the world and our position in it.

- At some point in adolescence, the brain changes tack, its role shifts from sponge to defender, and it now gives dominance to the internal environment: what we think and believe.

- From this point onwards, if we encounter information that challenges our worldview or a central tenet of our identity, we become defensive and our brains go into flight or flight mode, in the same way they would if we were physically under attack.

- This is due to the fact that we have set ideas about who we are, what we are like and what we believe – in effect, our identity has become ‘fixed’. Information that challenges our identity and understanding of the world, therefore, feels like a threat to who we are and to the reality that our brains have spent so long constructing.

- When encountering opposing views on topics that we regard as central to who we are, we subsequently retreat inwards or expend energy on staunchly defending why our views and beliefs are the ‘right’ ones.

- Indeed, research has shown that when our deepest beliefs are challenged, even if they are challenged with reputable scientific research, our response is to protect and defend these beliefs with such fervour that we end up believing them more than before they were challenged. This response has been termed “The Backfire Effect”.

- Now, this isn’t to say that our identity remains completely fixed over time – we can absorb new ideas, and new features might become central to who we are and form part of our new reality. But the same remains true – that whenever beliefs, values or opinions central to our identity are challenged we tend to feel like we are under attack.

It is really important to keep this knowledge of how our brains work in mind when we are connecting people and trying to build a sense of community because:

- We need to avoid putting people into a state of stress that makes them feel as if they are in danger, particularly if we cannot support them through the state of stress.

- If we want to help someone understand a view that runs contrary to a deeply held belief or a view they possess that is central to their identity, using facts or persuasive arguments is not going to cut it, we need to connect, listen and share. Once we make a bond with people and build trust, it is easier for them to empathise with and understand our perspective.

- We ourselves are fallible – our perspectives and beliefs that are linked to our identity might be preventing us from fully engaging with and understanding what others are saying.

- We might be wrong, but our brain might be duping us into believing that we are right!

Understanding a bit about our own identity and behavioural psychology can help us become better communicators, who are able to engage with potentially frustrating opinions more effectively, and who are open to learning and questioning our own beliefs. Such understanding also encourages humility – we may not be as ‘right’ as we think or feel we are.

If desired, use these questions to reflect on the content contained above:

- Did you find any of the information you read surprising, interesting or troubling? If so, what was it and why?

- Have you ever had beliefs central to who you are challenged? What happened? Did you become more set in your views?

- Have you ever challenged beliefs central to someone else’s identity? What happened? Did you notice this “backfire”?

- Will the information contained above impact how you communicate with others? If so, how? If not, why not?

Want to learn more about the brain and the way our mind operates? Have a look here:

- MIT Press Brain and Culture Blurb

- ‘The Backfire Effect’ Article: You Are Not So Smart

- ’The Backfire Effect’ Podcast: You Are Not So Smart

Power & Privilege

"Without community, there is no liberation.”

Audre Lorde

Introduction

What & why?

The concept of privilege - and the power that comes with it - is better understood than ever before. But it remains a sensitive topic in many situations. Members of the UK-based New Economy Organisers Network (NEON) seek to make issues of power and privilege easier to discuss and resolve within a campaigning context, and so produced this guide for organisers and activists to use within their own groups and organisations.

Though written for campaigners who hope to practically tackle power and privilege, this guide may also be of use to people who have a general interest in deepening their own understanding of the subject.

What to expect?

This guide contains some tried-and-tested tools and techniques that will help NEON members who are committed to creating truly inclusive spaces by challenging harmful behaviours (including their own) that reinforce certain privileges. The (by no means exhaustive!) content included comes from a variety of sources and features numerous articles, useful skills, tips on starting conversations around power and privilege, and ideas on using the resources you already have to contribute to liberation struggles. If you know of campaigners and activists from beyond the NEON community who are looking for help on this front, this is for them too. This guide is the start of a conversation, not the conclusion of one - its authors welcome suggested contributions from any readers with practical tips to add.

Who is it for?

This guide is for people who are seeking to deepen, share and open up their existing awareness of power and privilege with others - be they colleagues, fellow activists, or friends and family. We hope to offer another edition at a later date for those who are unfamiliar with the concepts outlined here, but curious to learn more.

A note on discomfort

Power and privilege can be uncomfortable or upsetting to explore when it relates to your own advantages. This is natural and if you stick with the challenge at hand, the feeling can become something much more positive.

Power & Privilege

What do we mean by power?

- The ability or capacity to do something or act in a particular way.

- The ability or capacity to direct or influence the behaviour of others or the course of events.

Here, we use the word power to particularly describe the inherited and learnt abilities and behaviours that help people influence their community and wider society. Power itself is neutral. In an abstract sense power can damage or strengthen a community, sometimes both at once. It’s all about being mindful to how power is applied.

Campaigners are increasingly able to recognise and seek to understand their own power, or lack thereof, and understand how they can use it for the benefit of creating inclusive communities.

- When you speak in a group situation, are you listened to? Do you create space to listen to others?

- When you propose a new idea, is it explored? If someone else offers you a new idea, do you give it room to be heard?

- When people say something you disagree with, do you listen and does the way you address it result in change? When you say something others disagree with, is it heard and does it result in change?

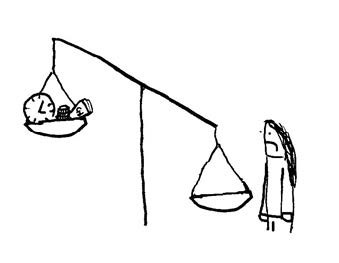

For many of us, understanding power and privilege will be a matter of seeing both sides to this - how we are simultaneously disempowered and empowered by social structures and deep, embedded cultures, and how we can disadvantage others whilst at the same time being disadvantaged ourselves in other contexts.

What do we mean by privilege?

Privilege refers to the collective advantages that a person can inherit from birth and/or accumulate over the course of time.

These advantages aren’t innate - they’re constructed by the society in which they exist, and can be seen wherever there are normalised power relations. Everyone is privileged in different ways - your own privilege may lie within your genetics, upbringing, current circumstances, or luck. Some are within our control, and some are not.

Privilege is also related to context - you can enjoy advantages in one culture or social setting that can easily become disadvantages in others.

It's worth taking a lesson from critical race theory, in part to understand white privilege, but to consider others too. This sees racism as an endemic part of society, deeply ingrained legally and culturally, which means it tends to look normal. Formal equal opportunity projects can remedy extreme forms of injustice but do little to deal with the business-as-usual forms of oppression. In such a context, claims to objectivity and 'meritocracy' act as camouflages for inequality.

Why understanding power & privilege matters

We all know that white hot feeling of injustice - we’re activists and campaigners, it comes with the territory. The grassroots groups, trade unions, faith groups and NGOs that many of us might be members of - or work at - understand that it’s important to call out organisations that use their power to treat people badly. If we don’t call out the Home Office or Shell, who will?

A sharper view of power and privilege will help us spot more injustices to fight. You have to see it first to tackle it. Moreover, always focusing on what's wrong outside of your organisations and campaigns means that problematic power structures in our own movements, organisations and groups often go unscrutinised. We are part of an unfair system, and it takes active work to not replicate it. Luckily, resources and advice that can help us do that are more accessible than ever before - and hopefully this guide will come in handy as a starting point.

Recognising injustices of power and privilege is an ongoing process. We've all spent many years adapting to inequality and it can take a while to challenge it. This isn't a free pass to dawdle, but rather a challenge to keep at it and get used to making an awareness of power and privilege an everyday occurrence. If you’re working through this personally, you might want to keep a diary of times where you catch yourself inadvertently being sexist, racist, taking a cis-centric view, lacking understanding of disability issues, or similar. Even if it's only a mental note, go back to these thoughts and make them every day. If you're working with a group don't just run a one-off diversity awareness training event, but schedule regular discussions where you ask colleagues to check in with an example of a time they spotted power and privilege at play, and an example of something new they are trying to help tackle it. Since the Stephen Lawrence case, we've talked about institutional racism and, on occasion, institutional sexism too, the way in which groups and organisations may inadvertently be structured to exclude, and may, gradually be reformed. Try to work towards a position where you recognise the institutional privileges around you, and try to shift to be institutionally aware of power.

Redressing privilege ultimately means creating a new kind of freedom - feminist Kay Leigh Hagan sums it up for multiple strands of liberation thinking when explaining how evolving gender norms brings benefits:

For both men and women, Good Men can be somewhat disturbing to be around because they usually do not act in ways associated with typical men; they listen more than they talk; they self-reflect on their behaviour and motives, they actively educate themselves about women's reality by seeking out women's culture and listening to women…

They avoid using women for vicarious emotional expression... When they err - and they do err - they look to women for guidance, and receive criticism with gratitude. They practice enduring uncertainty while waiting for a new way of being to reveal previously unconsidered alternatives to controlling and abusive behaviour. They intervene in men's misogynist behaviour, even when women are not present, and they work hard to recognise and challenge their own.

Perhaps most amazingly, Good Men perceive the value of a feminist practice for themselves, and they advocate it not because it's politically correct, or because they want women to like them, or even because they want women to have equality, but because they understand that male privilege prevents them not only from becoming whole, authentic human beings but also from knowing the truth about the world...They offer proof that men can change.

Kay Leigh Hagan in The Will To Change: Men, Masculinity, And Love by bell hooks

Getting Started

If you feel like the only person in your organisation or group that cares about addressing power and privilege issues, it’s very daunting and can feel lonely. Here are ways to get the ball rolling before you dive into tricky conversations with those who currently hold power.

Find an ally

Who is the most open to conversations about these topics? Start with them - it’s possible that they feel as strongly as you do. If they’re cautious but open-minded, make time to chat about your shared perceptions of power and privilege. Exploring this may lead to a deeper alliance that enables you to share ideas, support each other and change the wider culture together.

Gather research

If there have been instances where people have been systematically disadvantaged in some way, get the background on this. Find out about recruitment practices and sound out what most people’s take on diversity is. Is it a sore point? Something they feel they do well already? Or not on their radar? You can shape your approach accordingly.

Use existing procedures

Raise concerns with your trade union representative, staff forum convenor, or a member of your group that holds power over setting agendas and facilitation. See what kind of structured support they can offer you.

Start team-wide conversations

If you feel confident about raising the topic and proposing a meeting to discuss power and privilege within your campaign group, department or organisation, take that leap! Making it a series of workshops or conversations will help develop a sense of shared awareness and accountability.

Skills & practices

Here are some practical things you and others can do to address privilege-related problems within your sphere.

Check out the linked articles for further detail.

Active listening

‘The opposite of listening is preparing to speak’ - Three Faiths Forum.

Active listening is a skill in which the listener remains silent until the speaker finishes, then feeds back to the speaker what they have heard - this will help confirm what has been heard and allow both parties to ensure they have the same understanding.

Active listening is a key practice to make sure certain voices are not dominating in meetings, workshop spaces, etc. It’s a great habit to practice if you’ve ever caught yourself talking over someone else, and opting to silently listen to someone is a good way to earn their trust. Here are a couple of articles to help you hone your active listening skills:

Facilitating

Facilitation is the practice of adopting a neutral position within a meeting or workshop in order to help people move through a process together and draw out the opinions and ideas of the group members. When you become a facilitator, you can ensure that everyone in the room has the chance to participate.

Reflective practice

The habit of thinking about the words you’ve said and the actions you’ve taken, considering what happened next, and using that experience to improve your response to similar situations in future.

Stepping back

If you have privilege within the group dynamic, use it to make speaking room for those who tend to go unheard. For example, if you are in a group where you’ve contributed lots but there are others that are yet to do so, you actively say ‘I’m aware of how much I’ve spoken already so I’m taking a step back’. At a higher level, it might mean turning down offers to speak on panels with an unrepresentative line-up, and suggesting alternative contributors in your place.

Being an ally

An ally isn't just something you become - it’s something you do! If you actively challenge oppressive behaviour towards marginalised groups that you don’t identify with, you’re practicing allyship. So listening to someone who describes being marginalised is allyship. Educating yourself on structural oppression is allyship. Stepping back from opportunities in order to make way for underrepresented people is allyship.

The following articles on being an ally are very useful:

- [Franchesca Ramsey’s 5 tips on how to be a good ally](http://www.bustle.com/articles/53103-franchesca-ramseys-5-tips-on-how-to-be-agood- ally-pay-attention-privileged-people)

Self-care

This is basically giving yourself a break - switching off, forgetting the struggle for a little while, and doing whatever brings you a sense of wellbeing, no matter how brief or frivolous it may be. Being tired and stressed leads to illness, mistakes and total burnout.

For example, if you’re working to a major deadline around a planned action, whether a small occupation or a large march, self-care can be as basic as stepping out for a walk or going for lunch with your fellow stressed-out campaigners.

You no doubt know what works for you. Keep making time for it, savouring it, and remembering that ‘Caring for myself is not self-indulgence, it is self-preservation, and that is an act of political warfare’ (Audre Lourde)

You may find the suggestions in these articles a helpful starting point:

Attributes that will stand you in good stead

Patience

Learn to recognise when you find listening to the concerns of others difficult, and then learn to manage your reaction. It’s important to acknowledge the validity of people’s thoughts and feelings even when they don’t match your own perspective. Wherever you can, opt not to derail the conversation.

Self-awareness

Questioning yourself and considering the way you interact with others gives you a chance to subvert traditional power dynamics.

Showing solidarity

You might hear the word ‘solidarity’ a lot - it’s the act of standing alongside others fighting for a cause that often you aren’t affected by but wholly support. Understanding what it mean to stand in solidarity alongside others will help you do it better.

Resilience

We all mess up, make badly judged comments and reinforce crappy power dynamics from time to time. You’ll call people out, and it’ll be awkward at first; perhaps you’ll get called out another time, and it’ll be tough in a different way - but learning to adjust your approach to dealing with calling out or being called out will enable you to make society fairer for everyone.

Tools & techniques

Tools and techniques you can use to understand, confront and challenge the problems that arise. If you have something to add, do let us know – this is just the tip of the iceberg!

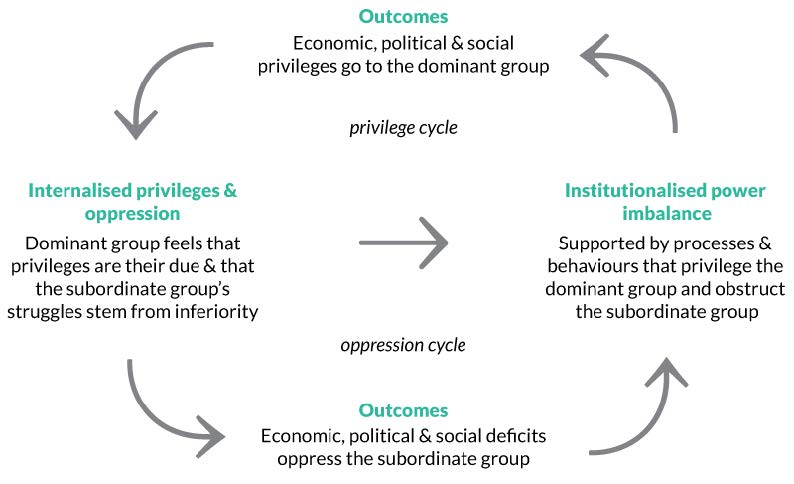

The cycle of oppression

You already have a sense of how identity can work in your favour or against it, but it’s possible that this is still unclear to those you work alongside and requires closer analysis. A great tool for exploring this is the cycle of oppression - a simple model that is highly relevant to discussions you have about power and privilege.

For example, if you’d like to discuss whether new recruits require a higher education qualification, you could use this model to explore why employees who have degrees feel uncomfortable about hiring someone who has taken a different approach to learning.

Oops/Ouch

This is a technique used by the interfaith charity 3FF in their education work. The idea is to create space for people (particularly young people) to explore ideas even if their language isn't perfectly sensitive first-time. 'Oops' allows somebody to rephrase something which they realise might be offensive after they said it, while 'ouch' flags up a painful reaction to a comment.

E.g.: Person 1: ‘Oops - I’d like to amend the phrasing I used as I think the term x expresses my meaning more clearly.’

N.B. this technique is designed for facilitated spaces where the group has gone through a process of agreeing ground rules (setting a safe space). Also, the assumption is that people are speaking with good intentions and causing offence accidentally – while this usually holds in 3FF's youth and education work this may not be a safe assumption in other environments.

Behaviour, Impact, Feelings, Future - BIFF framework

A simple method of speaking to someone about a disagreement or issue that you have had with them, making sure you focus on how their behaviour has affected you and how they can do things differently next time.

- Behaviour: ‘When we met to discuss tactics, I noticed that you spoke over me a few times

- Impact:...until it got awkward and I stopped making suggestions.

- Feelings:...To be honest, it made me feel really frustrated.

- Future:...I wanted to let you know so that in future, giving others space to speak will help with keeping everyone motivated to make this project a success.’

More about BIFF here.

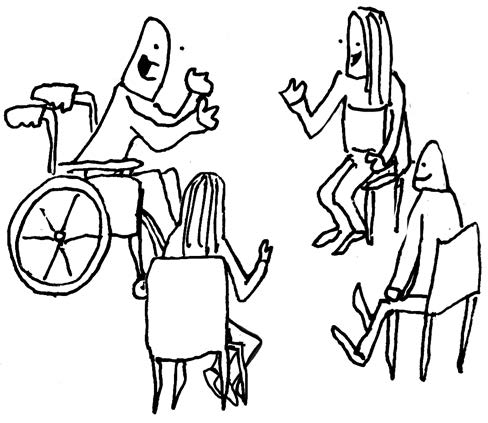

Theatre of the Oppressed

Sounds dramatic but is actually pretty good fun, and gives participants a chance to learn through acting out scenarios rather than talking, and identify the role body language plays in power dynamics.

Read more about Theatre of the Oppressed here.

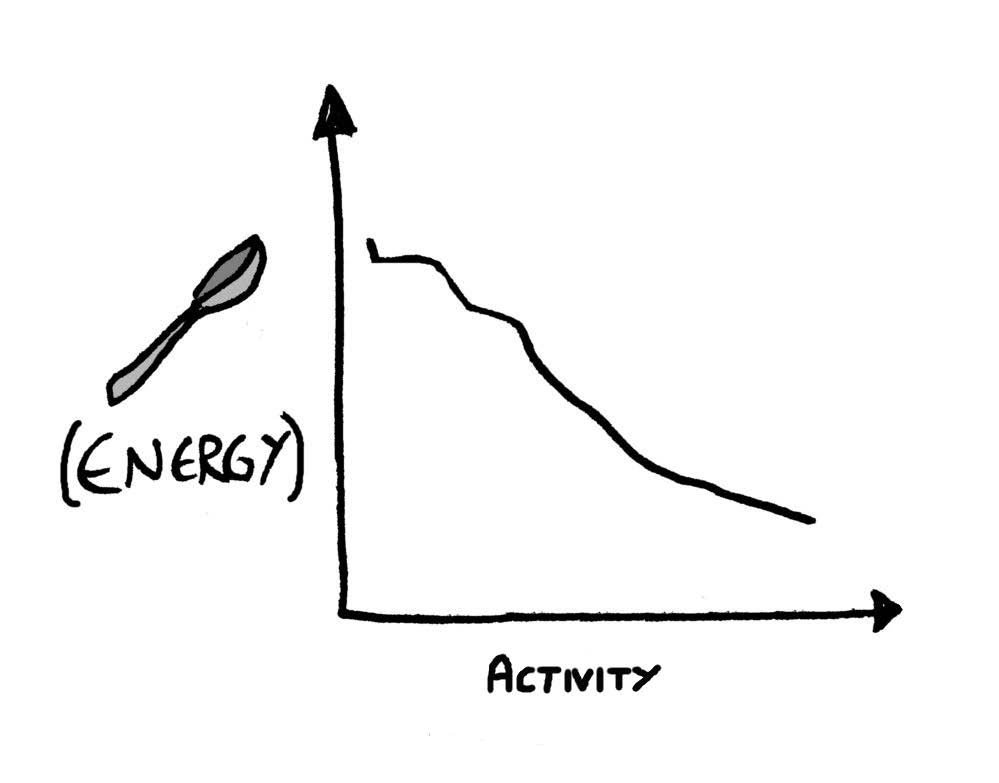

Spoon analogy

This illustrates the challenges that everyday living presents for disabled people and people with a chronic illness. You provide the participant with, say, 12 spoons - each represents a limited unit of ‘energy’ for a normal day. Ask them what they have planned for tomorrow, and remove a spoon for each activity they mention, and ensure they start right at the beginning - from getting up to eating breakfast.

The goal is to have some left for the next day so they can stay active - so if they run out of spoons, their only option is to rest. You don’t really need spoons to do this - the metaphor is enough for most people!

Making Use of What You’ve Got

There are things you can do with what you already have. Using your resources (financial and otherwise) more efficiently contributes to tackling inequality, both in everyday situations and at a larger scale - within your organisation or group, within your movement, and even within your friendship circles.

Energy

Energy is the main resource that we have as campaigners - we rely on it to get through times of little funding, little capacity and sometimes little motivation. It’s a precious resource, so where does it get spent?

- A group of local campaigners with no funding puts out a call for support. They need people to help them occupy a building, but all help is welcome. You’re stuck in the office but show support by tweeting their petition and boosting the profile of their occupation on Facebook. A few weeks later, you’re able to go in person to support another occupation.

- You are working on two projects but you’ve been unwell and want time out to recover. You continue supporting project A, which needs someone with your skillset to help out. You temporarily step out of project B, which although you’re more passionate about has lots of people with the same skillset as you contributing regularly. You’ll get involved with project B at a later date.

Time

Not so different to energy. Some people may have a work/family situation that gives them almost no free time, but those with more time have a privilege that can support others.

- A group of campaigners put out a call for someone with expertise in a certain policy area to help them understand the implications of government policy on their campaign. You're in a period of quiet at work so have a few hours to look over the policy and help the group.

- You have a Saturday free, so you and a friend are planning to spend it doing a round of the museums. The day before, you hear that there's a rally taking place outside Parliament. You don't want to change your plans but you know the rally is important. You decide the go to the rally, persuade your friend to join you and spend a couple of hours at a museum once it’s over.

There are many grassroots groups, organising with small amounts of money and on a voluntary basis, that regularly put out call outs. Take a look at their websites / social media pages for more information. Groups include: UK Uncut, Sisters Uncut, Focus E15, Sweets Way Resists, Boycott Workfare, Disabled People Against Cuts, Reclaim the Power.

Money

Where work is funded, invite the group involved to use money in a way that supports a fair distribution of power and resources.

- If no more staff can be hired to work on equality-related projects, can this work be included within the job descriptions of existing staff?

- If the cost of a highly desirable venue pushes up ticket prices, what provision can be made for unwaged attendees?

- If there is little expertise on activism within your organisation, but a will to support it, could financial contributions be made to expert grassroots funders like Edge Fund?

Spaces & materials

Do you have physical space and spare materials which you can share with groups that might not have much money and very little access to spaces for meetings and organising activities?

- Perhaps you have a spare desk which you can lend to those without an office space to use a few days a week, or a meeting room that can be booked out in the evenings.

- Or maybe you could print some flyers for a grassroots group.

Keep an eye out for requests amongst your network and offer help where you can.

About This Guide

This guide has been produced by the New Economy Organisers Network (NEON), a UK-based organisation that exists to strengthen the movement working to replace neoliberalism with an economy based on social and environmental justice. NEON runs training courses, campaign hacks, political education programmes, socials, and a mailing list, amongst many other things.

NEON is made up of a community of activists, campaigners and other types of change makers, and this publication has been written by members who are determined to improve the collective understanding of inequality in our activism and daily lives. Tackling power and privilege is fundamental to NEON projects, and we work towards three broad goals:

- Making the NEON community actively aware of the impacts of power and privilege within society.

- Strengthening the NEON community by working towards making it more representative of society.

- Supporting members of the NEON community who are experiencing and/or tackling oppressive behaviours within their campaigns and wider society.

NEON started life as a project of the New Economics Foundation (NEF) but has since set-up as an independent not-for-profit company. The network is coordinated by a small staff team with projects run in collaboration with members and their organisations. This introductory guide has been written in collaboration with NEF.

If you would like to contribute to this work, please get in touch with us: jannat.hossain@neweconomics.org

Useful links

Here’s a list of articles, blogs, and videos that NEON members have found useful for discussing power and privilege. They can be used to deepen your own knowledge of an issue, but they’re also really handy to share with others that you are talking to about privilege.

This isn’t an exhaustive list and is ever-evolving - share your own eye-openers and we’ll add them in!

Websites

The following websites are every self-aware person’s dream. They contain a bountiful amount of articles and resources for anyone committed to understanding power and privilege better.

-

Everyday Feminism - a website dedicated to ending all forms of discrimination and oppression using intersectional feminism, in the US and beyond.

-

Edge Fund - an organisation trying to change the way campaigning groups are funded. They have a long list of reading on power and privilege.

-

Media Diversified - an organisation founded to challenge and change the media’s racism and lack of diversity – they regularly publish articles on structural oppression.

-

The F-Word - a website seeking to build community through discussions around contemporary feminism in the UK.

-

Transformation, OpenDemocracy - described as ‘Where love meets social justice’, this website has a dedicated section to intersectionality.

On Being Uncomfortable

-

4 uncomfortable thoughts you may have when facing your privilege [text]

-

Privilege discomfort: why you need to get the fuck over it [text]

Articles with Intersectional Relevence

-

How to manage privilege [cartoon]

-

How to be an ally [video]

-

Calling in: a less disposable way of holding each other accountable [text]

- ‘When I see problematic behavior from someone who is connected to me, who is committed to some of the things I am, I want to believe that it’s possible for us to move through and beyond whatever mistake was committed. I picture “calling in” as a practice of pulling folks back in who have strayed from us.’

-

When being ‘an ally’ gets problematic [text]

- ‘Being an ally isn’t a status.’

-

How to address conflict using the Behaviour, Impact, Feelings, Future framework [text]

-

Batman: how expectations alter who we are: This American Life episode [audio]

- Can other people's expectations of you alter what you can do physically? Alix Spiegel and Lulu Miller of NPR's new radio show and podcast Invisibilia investigate that question – specifically, they look into something that sounds impossible: if people’s expectations can change whether a blind man can see.

-

Edge Fund: models of power sharing [text]

- Examples of power-balanced funding for grassroots groups, with detail on the processes that organisations and activists used to work together in a mutually beneficial way.

-

Kyriarchy 101: we’re not just fighting the patriarchy anymore [text]

-

How to talk about privilege to someone who doesn't know what that is [text]

-

13 stunning photos capture how exhausting it is to deal with daily discrimination [text]

On Ability

-

Scope’s End The Awkward campaign resources [text and video]

-

Online accessibility tools [text]

-

7 ways to support friends when they’re mentally unwell [text]

On Age

-

Older people’s accounts of discrimination, exclusion and rejection [text]

-

Older women: has society forgotten how to value them? [text]

On Class

-

It's not "them" — it's us! [text]

- ‘A radical working-class friend tried to join a corporate globalization group...He soon quit in disgust. I wonder if the group members understood why he left.’ Here’s why:

-

On a plate: a short story on privilege [cartoon]

-

Feedback from campaigners: how to be an ally [text] By Class Matters

On Gender +

-

Men who explain things [text]

- The origin of the term ‘mansplaining’

-

What women have to do in order to be heard [text]

- ‘Men interrupt women, speak over them, and discount their contributions to a discussion with surprising regularity. Here’s how women should respond’

-

Transwhat? Tips for allyship [text]

-

35 practical tools for men to further feminist revolution [text]

On Race

-

White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack [text]

- This article is now considered a classic by anti-racist educators.

-

Reverse Racism (Fear of a Brown Planet) [video]

- Aamer Rahman: “The number-one feedback I get from the clip is, 'I've been trying to explain this to my friend, or a colleague, for years – and now I just send them your video.”

-

The difference between cultural exchange and cultural appropriation [text]

- Multicultural societies exert a tax on the cultures they borrow from, to varying degrees. But how much? Is eating sushi a form of cultural appropriation, if you aren’t from Japan? What about western trends permeating other cultures? This article provides insights into how privilege and context affects these issues.

-

White anti-racism: living the legacy [text]

- What does "white anti-racist" mean? How can guilt get in the way? And what's all this talk about being "colorblind"? Community activists share their thoughts and shine light on the concepts of comfort, power, privilege and identity.

-

10 simple ways white people can step up to fight everyday racism [text]

On Sexuality

-

The Queer 101 - the downlow on sex, sexuality and gender [cartoon]

-

GLAAD's resources for allies [text]

Quotes of interest

"There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives. Our struggles are particular, but we are not alone. We are not perfect, but we are stronger and wiser than the sum of our errors." —Audre Lorde

"If you have come here to help me, then you are wasting your time…But if you have come because your liberation is bound up with mine, then let us work together." —Aboriginal activist saying

"It is very tempting to take the side of the perpetrator. All the perpetrator asks is that the bystander do nothing. He appeals to the universal desire to see, hear, and speak no evil. The victim, on the contrary, asks the bystander to share the burden of the pain. The victim demands action, engagement, and remembering…" —Judith Herman in Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence—from Domestic Abuse to Political Terror

"If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there's no progress. If you pull it all the way out that's not progress. Progress is healing the wound that the blow made. And they haven't even pulled the knife out much less heal the wound. They won't even admit the knife is there." —Malcolm X

"The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house." —Audre Lorde

"It is part of our task as revolutionary people, people who want deep-rooted, radical change, to be as whole as it is possible for us to be. This can only be done if we face the reality of what oppression really means in our lives, not as abstract systems subject to analysis, but as an avalanche of traumas leaving a wake of devastation in the lives of real people who nevertheless remain human, unquenchable, complex and full of possibility." —Aurora Morales

Reflecting on Identity Privilege

If you’ve moved in any social justice circles, or even if you haven’t, you’ve probably come across the concepts of privilege and oppression. The idea that some people are innately advantaged over others just because of who they are.

You may be thinking, duh? Perhaps it’s obvious to you, but for many this idea of axes of advantage and disadvantage can often appear quite abstract, particularly if we are not aware of any immediate effects on our lives. Some of those effects are so deeply entrenched in our culture that we don’t even notice them.

It takes hard work to actively dismantle the harmful dichotomies and systemic oppression that we have been shaped by but it is essential if we are to build strong, resilient and compassionate communities. First, we need to begin by acknowledging and ‘checking’ our own privilege.

This reading will help you reflect on identity privilege, what it means and how we can move forward. It has been divided into the following sections for ease of reference.

Understanding Privilege

Our relationship to Privilege

You are privileged.

What’s your reaction to that statement? Your initial, knee jerk reaction? Sit with that feeling for a moment, let it fill you up. Really examine what’s driving that emotion.

Quite possibly, you don’t see yourself as a privileged person. Many of us do not actually feel privileged. We may have jobs we don’t like, be in financial situations which are less than ideal, and/or we may be being mistreated and undermined by people around us.

It’s completely valid if you hear an ‘accusation’ of privilege and feel defensive, confused, even angry. How can we be privileged when our lives are so uncomfortable and when so many things are out of our control?

The answer is that these things are relative. We all experience privilege within the context of our own experiences. It’s not always possible to see the ways you are advantaged because that would mean understanding something hidden, a series of challenges and hindrances that are invisible to us, unless we take a special effort to put ourselves in others’ shoes.

A right-handed person, for example, is privileged in that most equipment is made for them. They do not have to drag their hand through the ink when they write. They are likely to go through their daily lives feeling as if the hand they use most is irrelevant. They simply write, cook, drive and live their daily lives feeling as if the hand they use most is irrelevant.

A left-handed person conversely has the trouble of needing specially made tools and equipment to be made or purchased for them at additional cost. They must drag their hand through the ink when they write. As children they may have been chastised for doing ordinary activities in the way that feels right for their body.

A right-handed person may not think about their dominant hand because they don’t have to. This is what it means to be privileged. It’s about what you don’t have to put up with. So, by extension the right-handed person might not place any importance in being right-handed. They may not consider it a part of their identity. This is because it’s an example of a majority identity.

Most privileged identities are typical of the majority of people. They are seen as the ‘default’ people belonging to these dominant groups then, are never really forced to examine their place in the world and they grow up blind to the advantages they have over others.

Don’t Put Me In A Box: The Labels of Privilege

Our identities are very complex things. How you feel about yourself, what you consider defines you, or how your loved ones would describe is a closer representation of your true self. We certainly place greater stock on some parts of ourselves than others. We may be more comfortable with some parts of ourselves than others. We may have identities like ‘parent’, ‘artist’, ‘animal lover’, but these are labels we choose; labels we gain through patterns of behaviour and thereby don’t carry the weight of prescribed privilege.

This is not what we mean when we discuss issues of identity privilege. Identity privilege is any unearned benefit or advantage one receives in society by nature of their identity. Something you have just from the lottery of birth. Some examples are: Race, religious heritage, gender identity, sexual orientation, class/wealth, ability or citizenship status.

Identity privilege is connected to the way you are viewed by the people around you and your position in society. The privilege is related to the label on the box you have been put in that gives you a greater status or that allows you to access more opportunities than others.

If we accept this concept of privilege, then it follows logically that there is a flipside. Those who are diametrically opposed to the privileged identity are systematically oppressed instead. They are saddled with an unfair disadvantage due to something they cannot control.

The Lottery of Birth

It can be very easy to see the ways in which we are oppressed. Many of us are far readier to examine these than to face up to how we may be unfairly privileged over others since this can often carry with it many difficult emotions of anger, and guilt.

Consider these hypothetical people:

- Samuel and Fiona are comfortable walking down the street holding hands, they have no reason to fear retribution when they kiss each other. How might this be different for a homosexual couple?

- Hayley uses the women’s public toilets without hesitation. If Hayley was a trans woman, why might she have more trouble doing this?

- Daniel is confident the police exist to protect him and will treat him with respect. If Daniel was black, would this be the case?

- Martha never worries about whether she is going to be able to enter a building. If Martha was a full-time wheelchair user, she probably would. Why?

- Brian is unafraid to walk home by himself at night. Do you think his sister Mia would feel the same? Why?

- Tina has been given a parking fine. She considers this only a minor inconvenience. Why do you think this might be?

What have you identified when considering the above scenarios and questions?

Why don’t you try and do the same exercise with yourself – it can be effective to compare notes with others and discuss your different experiences.

Power structures

Now that we understand the idea of identity privilege it’s important to examine how our society is set up to favour some identities over others. This favouritism is connected to the mechanisms and structure of oppression, and the allocation of power and how it is wielded.

Majority identities hold the power by virtue of their privileged position. They serve as the measure of what is normal, real and correct. Much of their power links to their ability to define reality, and this happens on every level of society.

Individual beliefs and values align with this idea of reality, which is skewed in favour of the dominant identity. These beliefs and values are reinforced on an interpersonal level through actions, language and our interactions with others, and then on an institutional level through our political system, which shapes public policy, the legal and education system, and the workplace. the media, which is shaped by our power structures and which reinforces them, also informs collective ideas about who or what is ‘right’, who or what is ‘attractive’ and who or what is ‘dangerous’. These ideas are therefore integrated into our individual belief systems as we grow, and help to create a self-perpetuating and self-propagating system, which builds and sustains itself from one generation to the next.

We can see then, looking at history, how things can change drastically when people begin to question the collective ideas they have been raised with.

The Face Of Oppression

Oppression can take many forms, and can lead to people being scrutinized, marginalized and isolated throughout their lives. Oppression gives life to prejudices, which often form as a means of justifying oppressive structures: women are oppressed by the patriarchal and sexist structures in society, people of colour are oppressed by white supremacy and racist structures.

An important point is this oppression happens at all levels, as we have just seen, reinforced by societal norms, institutional biases, interpersonal interactions and individual beliefs. Even more important: we are all complicit. Some of us may be more complicit than others, but we can all be oppressors, just as we can all be oppressed.

This is a tough pill to swallow. It’s one step beyond telling people they are privileged, to tell them they are also automatically then, oppressors or members of an oppressive group.

Most white people, for example, don’t see themselves as racist. They see racism as a prejudice leading to hateful, violent actions, which horrifies them as they would never do that, they resent being slandered as a racist.

Now while it’s true violent attacks are one manifestation of racism, there is so much else that goes unseen beneath the surface. The violent attacks are only made possible by the structures of power that support them. If white people grow up seeing people of colour as alien, even as dangerous or as ‘less than’ then they begin to treat them that way. Either subtle undermining or direct bullying may take place right into adulthood as people act on their beliefs, and then the laws, the public institutions that are built and maintained by the same people that have unknowingly racist beliefs propagate discriminatory practice – this may not be as overt (i.e. Jim Crow laws) anymore but rather covert (disproportionate incarceration of black offenders) – and these ideals and re-disseminated via the media.

“The problem is that white people see racism as conscious hate, when racism is bigger than that. Racism is a complex system of social and political levers and pulleys set up generations ago to continue working on the behalf of whites at other people’s expense, whether whites know/like it or not. Racism is an insidious cultural disease. It is so insidious that it doesn’t care if you are a white person who likes Black people; it’s still going to find a way to infect how you deal with people who don’t look like you.*

Yes, racism looks like hate, but hate is just one manifestation. Privilege is another. Access is another. Ignorance is another. Apathy is another, and so on. So, while I agree with people who say no one is born racist, it remains a powerful system that we’re immediately born into. It’s like being born into air: you take it in as soon as you breathe.

It’s not a cold that you can get over. There is no anti-racist certification class. It’s a set of socioeconomic traps and cultural values that are fired up every time we interact with the world. It is a thing you have to keep scooping out of the boat of your life to keep from drowning in it. I know it’s hard work, but it’s the price you pay for owning everything.”

Draw a racist. What do they look like? What are they doing? Why are they the way they are?

The intention of this is to examine the ‘racist’ label critically, we may have an idea of what a racist person is, what they look like, what they do but consigning racism to a limited caricature prevents us from examining real systemic racism. The ‘racist’ label is limited. A better way of looking at it is that we are all ‘racist’ to a certain degree as we are unknowingly raised with racist ideals in a fundamentally racist society. Some people may be more overtly racist than others but we are all complicit.

Talking about oppression as an individual act prevents us from fully understanding the problem and prevents us from self-improvement as we are constantly looking for a mythical responsible party to which we can ascribe all the blame. This behaviour locks the whole thing into place.

We are all crew

There are two important things to bear in mind when thinking about this:

- This system is no one’s fault.

- This system harms everyone.

In this article we say society favours some identities over others rather than society favours some people over others and there’s a reason for that seemingly pedantic use of language. Because even those who seem to benefit rarely benefit holistically as a human person. A privileged person is locked into their position as much as an oppressed person. They are expected to conform to a certain standard, display certain characteristics and do their part to keep the status quo. Those who deviate can often be harshly punished as if in alignment with those they should be pitted against.

People may have a lot of power, but this is not deliberate, and they don’t have to work very hard to maintain it. We are all assigned platforms, positions in society which we did not choose. Unearned doesn’t simply denote that we don’t deserve something, but that we cannot be held accountable for having it.

What matters is our actions going forward. We cannot change the past, but we can continually challenge our attitudes and refuse to participate in a system of sustained inequality.

What Can We Do?

We can push for diversity. Diversity is important, particularly where groups are concerned with transformative community engagement. If these groups are too homogeneous then they can quite naturally end up serving only the needs of their dominant identities. A lack of diversity can cause issues to be forgotten and it is harder to reach those who may feel they are not represented. These divisions can be ruinous. How can we possibly work together with people we don’t trust? Or people we don’t really respect?

We need to understand the power structures that exist in society and our roles within them so we can do the continuous and introspective work of dismantling them and coming together as equals, valuing one another. We must build the capacity to listen and consolidate our feelings. This is the key to preparing ourselves to be part of a regenerative culture.

Personal Visioning

The visioning process helps you to connect with your strengths, your values and what it is you want to achieve, be it in life, in the next few years, or in the process of reaching out to others in your community. Dedicating time to considering what your goals are and how they align with who you are is a great way of staying focused in your actions, of increasing drive and dedication, and of staying inspired. Visioning is also a wonderful way to stay grounded, whatever life may throw at you. Having done some exercises related to visioning it can then be very helpful to summarise your learning, ideas and hopes by writing a vision statement, which you can then refer back to as and when you need to.

It is important to note that having a personal vision statement can mean different things to everyone: some may find their vision change over time, others that vision is something they return to as a source of support. Regardless of the role the vision statement ends up playing in your life, the process of creating one is profound, meaningful, and helps you connect with your values and who you are.

The activities outlined below will help you engage in visioning and take you through the process of writing a vision statement.

This document has been divided into the following sections for ease of reference. You don’t need to complete all of the activities listed, do whatever feels right, but if you are struggling with visioning, doing more of them can help you organise your thoughts, feelings and ideas:

Understanding Your Values

Aligning our actions with our values helps us to find meaning in life. It can, therefore, be really useful to try and understand what our core values are. The following exercises are designed to help you do so.

Hypothetical Advice

- Imagine that you are talking to a teenager who is seeking advice because they are concerned and confused. They feel pressure to follow a career that they are unsure about, but they know that pursuing that career will secure them financial stability and will make their family happy.

- What three pieces of advice would you give the teenager?

- Why would you give those pieces of advice?

- What do they tell you about what you value?

A Meaningful Memory

- Think back to a moment in your life that has become a meaningful memory. This could be a holiday, an event, an experience, a role, or anything that comes to mind.

- What was going on during this time?

- How did you feel? Why?

- Was there anything in particular that you were able to do or anything that stands out? If so, what?

- What does this memory tell you about what you value?

The Ideal Day

- Imagine your ideal day from when you wake up to when you go to sleep.

- What happens at each stage of your ideal day?

- What do you do?

- Who do you see?

- How do you feel?

- What are you working towards?

- What does this ideal day tell you about your values?

Your Values

- Using your ideas from the previous activities, write down five values that you think feel are important to you.

Identifying Your Strengths and Areas for Improvement

It can be really helpful to think about your strengths and the areas in which you can improve when visioning – the process enables you to create realistic goals that play to your abilities, whilst also encouraging you to think about what it is you would like to get better at. Balancing playing to your strengths, whilst working on areas in which you want to grow can help you reach your potential.

Identifying Your Strengths

It can sometimes be hard to identify our strengths, particularly in cultures that discourage or look down upon self-promotion, but it is important to remember that we all have our strengths and it is not arrogant to identify them or to be proud of them. Strengths come in a range of forms – they might be connected to your values, your roles in life, your outlook, personality or the way you connect with others, and/or your skills.

Use the following prompts to help you identify your strengths:

- Values

- What values do you possess that you are proud of?

- Why are these values something to be proud of?

- How might these values be a strength?

- How have they impacted your life?

- Roles

- What roles do you take on in life?

- In what ways are you good at these roles?

- What skills have you developed as a consequence of taking on these roles?

- How are these skills a strength?

- How have they impacted your life?

- Outlook & Personality

- What about your outlook in life or personality are you proud of?

- Why are you proud of these?

- How are these attributes a strength?

- How have they impacted your life?

- Relationships

- What about your relationships with others are you proud of?

- Why are you proud of this?

- How are these relationships a strength?

- How have they impacted your life?

- Skills

- What skills do you have that you are proud of?

- Why are you proud of these skills?

- How are these attributes a strength?

- How have they impacted your life?

Now you have identified your strengths in a range of areas, write them down in a coherent list. You might wish to start your list with the line “My strengths are…”

Identifying Your Areas for Improvement

We are not static, we are constantly responding to the environment around us, adapting, learning and growing. Indeed, one of the most magical things about existence is that we have the capacity to improve and to respond to what we learn, be this in developing a new practical skill or in gaining a greater understanding of ourselves and how we relate to people. The point of this exercise is not to make you feel bad about the areas in which you can improve, but to feel inspired about what you can do and how you can grow.

Use the following prompts to help you identify your areas for improvement:

- Outlook & Personality

- What attributes would you like to develop?

- Why would you like to develop these attributes?

- How would developing these attributes impact your life?

- How might you go about developing these attributes?

- Relationships

- What about your relationships with others would you like to improve?

- Why would you like to improve this?

- How would an improvement in these areas impact your life?

- How might you go about improving your relationships?

- Skills

- Which skills would you like to improve or develop?

- Why would you like to improve or develop these skills?

- How would an improvement in or development of these skills impact your life?

- How might you go about improving or developing these skills?

Now you have identified your areas in which you would like to improve, write them down in a coherent list. You might wish to start your list with the line “I would like to grow by...”

Sketching Out Your Vision

When responding to the following prompts, you might want to think about your values, your strengths, and the areas in which you wish to grow.

The Magic Wand

Imagine that you have a magic wand then enables you to shape your future and create the kind of life that you want for yourself and for others around you.

- What would you be doing in the next:

- Three months?

- Six months?

- Year?

- Five years?

- Ten years

- Twenty-five years?

What do your responses tell you about what you would like to achieve in life?

The Wheel of Life

- Creating a wheel of life can be an incredibly useful exercise to help you think about what areas in your life you wish you improve and about where you want to go next.

- Create your own Wheel of Life, using this template and reading the accompanying instructions to guide you through the exercise.

A Vision Board

According to the Coaching Tools Company, vision boards are “a way of teaching our mind to focus on the things that are important to us, and can be a great way to connect with our subconscious wants, desires and needs - and make them conscious”.

What is a vision board?

“A Vision Board is simply a collective name for a wide variety of inspirational maps (a collage) that we create from pictures. The map can be WHO we want to be or HOW we want our lives to be, and is a visual representation of our goals and dreams – a powerful way to make our aspirations more tangible and attainable...The very act of CREATING the vision board tells our mind what’s important – and it may just draw our attention to something we might not otherwise have noticed.”

How to create a vision board:

- Find a big piece of paper and some old newspapers or magazines.

- Cut and collect pictures, words, quotes, anything that inspires you or catches your eye, and then stick them on the big piece of paper, arranging them how you want.

- Do not analyse what you are selecting or why, just cut, stick and create: let your mind run free and follow your feelings.

- Use images, use colour, use words that matter to you, make it vibrant and make it inspirational. Your vision board should excite you!

- Allow yourself 1-1.5 hours for this process

Once you have made your vision board, you can either put it away somewhere and return to it in the future, however many months or years down the line, or you can put it somewhere you will see it every day to remind, inspire and focus you. If you do the latter, you may want to allocate a set amount of time to look at the vision board each day, to review it and feel excited by it.

Writing Your Vision Statement

A vision statement can ensure that you keep sight of what is important to you in life; it can provide clarity for the future, whilst allowing you to stay focused in the present and can act as a support when you are feeling distracted, down or uninspired. The vision you create does not need to be perfect nor does it need to be held back by what feels possible where you are right now: be creative, have faith in yourself and don’t worry about sketching anything out perfectly. Perfection doesn’t exist and things are always a process.

Vision statements will be different for everyone – some people might write a page, others a paragraph, and others a sentence or two. Do whatever feels right for you. If you want some inspiration, have a read of Oprah Winfrey’s vision statement. Her vision is “to be a teacher. And be known for inspiring my students to be more than they thought they could be”.

To help you get into the right frame of mind for writing your vision, plant yourself in the present, and let go of whatever might be hassling you in your mind by first connecting with your breath. Listen to your breath and focus on your breath, and let your mind clear itself of concerns.

Next, think about the following:

- Your values

- Your strengths

- You areas for improvement

- Your areas of focus (as identified in your Wheel of Life)

Then start crafting your working vision statement to capture the things that are most important to you and the direction in which you would like to go. You might wish to include references to your values, strengths, areas of improvement and areas of focus; to connect to your passions or interests; and/or to root vision statement in time, thinking about something that you will do daily, as in the five principles of Reiki:

Just for today…

I will let go of anger

I will not worry

I will be grateful for all my blessings

I will work with honesty and integrity

I will be kind to all living beings

Write your statement in the present tense and have it highlight what matters most to you, what you stand for and who you are committed to becoming.

Once you have your draft of your statement, you might wish to put it to the side and let some time elapse before you review it. You might also wish to put it somewhere prominent for you to see, or review it a set time each week to help ground you and remind you about what matters to you.

Whatever your relationship with your vision statement, know that you can refer to it if you ever feel distracted, lost or confused, and that you can update it to reflect any changes in your values or ife aims.

Useful Links:

Ten Great Ideas for Life Visioning and Planning

How to Craft Your Personal Vision

The Five (5) Principles of Reiki Explained and How to Incorporate them in our Daily Lives

Building Courage

Courage is a sense of inner strength that enables you to persevere, despite fear or difficulty; it is a voice inside that encourages you to be brave and step beyond your comfort zone; it is a drive to speak out against injustice, even if your voice feels small and insignificant; it is something that we all have within us. Accessing the courage within, however, is not always easy, but it is important if we are to go out and connect with strangers in our communities. The good news is that the more we work on building up our courage, the more courageous we will feel and the easier once intimidating tasks become.

One of the reasons why it is hard to access the courage within is that we are not always encouraged to feel like capable agents in our own lives. It often feels like we have little choice in how society is organised and that we are too small to change things; this sense of powerlessness can fill us with self doubt. We also live in a society where it is the norm to criticise others, to shame them and ridicule those who put their heads above the parapet. This can create fear about being brave and bold, particularly as acts that require courage involve us taking ourselves out of our comfort zones and making ourselves vulnerable.

But courage is also about facing such fears. Often what we are afraid of us is connected to our insecurities: what we perceive as our failures and weaknesses. It is quite normal to avoid opportunities or procrastinate before engaging with important tasks if we are afraid of doing badly. We must acknowledge these fears and recognise when we are dodging tasks by hiding or taking on pointless work that fills up our time. When we remove mental roadblocks we are better able to take bold action.

And it is worth it: being bold and courageous has its rewards: it can help us achieve our goals, it can help us feel more confident in who we are, and it can open up new and exciting doors. It is also something that we can practice and get better at over time: courage does not suddenly grow within us, it needs to be nurtured. We need to flex our courage muscle in daily life and get into the habit of pushing ourselves in small ways that help make us braver and more resilient.

Here are some exercises to help you find that inner courage.

Acknowledge Your Emotions

Acknowledging and sitting with our feelings is important pre-work when building courage – they are there for a reason and they can help us better understand ourselves. It is therefore important to take time to recognise feelings, accept them and investigate them to learn about what is driving them. Understanding how we feel is a vital step in allowing us to process our emotions and let go of them; it also creates space for self-care, for ensuring we are looking after our needs.

As we build courage, we will begin to sit with uncomfortable emotions and gain a greater understanding of them and their effects on our bodies. Through this greater understanding of ourselves, we will be able to address our needs, which can make us more confident in moving out of our comfort zone and facing up to more challenging scenarios.

Next time you feel yourself overcome by any emotion, consider reflecting on your feelings using the following approach (you may find it useful to take notes with a pen):

R - Recognise the emotion/feelings

A - Accept the emotion/feelings

I - Investigate what is causing the emotion/feelings

N - Nurture the cause of the emotions/feelings (it is often an unmet need)

Reflect on Your Fears

There are healthy fears and there are unhealthy fears. Sometimes it is healthy and natural to be afraid: the fear we might be feeling is an instinct that keeps us safe from putting ourselves in dangerous situations. It is sensible, for example, to be scared of walking too close to the edge of a cliff as it can result in a fall.

More often than not, however, we find ourselves afraid to do things which are actually not that dangerous and may even be beneficial for us. We might be scared to ask a question, or speak out when we disagree with something, or to ask for something that will help us. We might be scared to go on a date, or try out for a new job. The reasons we are afraid are a little harder to pin down; they may feel unsafe to us: this fear is not centred around risk to life or limb, but more abstract worries – that we won’t succeed, that we’ll be rejected or embarrassed. Often our fears in these situations are linked to certain core beliefs about ourselves and/or to self doubt. We might think:

“My question won’t be interesting enough”.

“I will be criticised for not understanding enough”.

“I will be rejected because I won’t be good enough”.

It is important to think about our fears, identifying what causes them and the impact that they have had on past behaviour.

Identify Your Fears

By identifying what you are afraid of, you can empower yourself to act with courage and face such fears.

- Make a list of different things that you fear.

- Write down different things you would do if you did not have those fears.

- Discuss one of your fears with someone you know.

Identify How Fears Have Impacted Past Behaviour

Calling out these fears will be difficult and painful but it is important to do so if we are to understand what’s holding us back.

Take a pen and note down five situations in which fear or discomfort have stopped you from doing what you wanted to do. Then mindmap each of those situations, using the following questions to help you:

- What was happening in the situation?

- Why did you feel fear or discomfort?

- What reactions did you fear?

- Were your fears valid? How do you know?

- What were the consequences of your response?

- What would have been the consequences if you had followed through with what you wanted to do?

Step Out of Your Comfort Zone

Take a medium sized risk and see where it leads. If there is something you have been putting off, take the jump! It’s important to be gentle and patient with yourself and realistic about what you can accomplish, so maybe best not to go too big for your first time – but do make a conscious choice to take a risk. An act of courage does not need to be an enormous show or act, like standing up to speak in an auditorium in front of a thousand people. It can be a decision to smile at a stranger in the street or strike up conversation with a neighbour. Remember, overcoming our fears and building courage is a process, start small and see where you end up.

What you choose to do should be something that makes you nervous, not petrified with fear, and it’s a good idea to spend a while on this step, and to make a habit of whatever you are choosing to do before moving on.

Then reflect on the process. You may wish to use these questions to help you:

- How did it feel to step out of your comfort zone?

- How did the experience differ from your expectations?

- What did you learn about yourself?

Experience the New

Make a tiny change to experience unfamiliarity. This doesn’t need to be anything significant. You might, for example, choose to start the way in a different way by eating something different or changing your morning routine. Or, you could cook something you have never cooked before or buy an ingredient you have never bought. Or decide that you will spend one week saying yes to whatever suggestions come your way.

The idea of this is to break you out of any ruts you may be in, and to help you be more adaptable to change. Sometimes the familiar and the routines that we have become comfortable and make us averse to change, which can in turn prevent us from taking risks and being courageous.