2. Group Support

Group support is focused on enabling people to work with others in a supportive and empathetic way, and on creating group cultures which allow everyone to thrive, provide the emotional support that people need, and give people the skills to deal with conflict constructively.

- Overview

- Personal Reflections on Working in Teams

- Getting to Know One Another

- Tips on How to Give and Receive Feedback

- A Quick Guide to Holding Effective Meetings

- Building Healthy & Empowered Teams

- How to deal with conflict in your groups

- Holding Emotional Spaces

- Reflecting on and Tending Grief

- Listening Circles: Supporting Grief Online

- Making a Strong Working Group

Overview

What is group support?

This module is focused on enabling people to work with others in a supportive and empathetic way, and to create group cultures which allow everyone to thrive, provide the emotional support that people need, and give them the skills to deal with conflict constructively.

Why is this module important?

When working with others, it is really important that early on you clearly and honestly establish your expectations for yourself, for the team, for each other and for the project you are working on. Doing so can create a healthy working environment, in which people understand and respect boundaries, and work together for the collective success of your defined goals. Having such discussions initially also ensures that your relationships are built on openness and it can help you to deal with conflict constructively, as and when it arises.

Creating a team that emotionally supports those within it is also incredibly important as only does it ensure that people are looking after each other, it also enables the development of genuine connections, which can help to establish trust. Teams composed of individuals who care for each other’s well-being and who trust each other are far more likely to succeed and fulfil their aims.

Personal Reflections on Working in Teams

Working with others can be a magical, transformative and inspiring experience; it can help us reach heights that we would not be able to reach alone, and to constantly learn from one another, providing opportunities for growth and reflection. Much of our progress as human animals has come from our ability to work together, and the way we have shaped the world is evidence of this. But it can also be difficult to work in teams: we have to negotiate people’s feelings and perspectives, and forge relationships of trust and understanding. Teamwork is a complex plane to navigate and we no doubt all have different experiences of working with others: some of us may have enjoyed the process of connecting and working in teams, whilst others may have found it difficult to thrive in a team setting. We also all will have different levels of experience: whilst some of us may work in teams daily, others may not have done so since school.

Whatever your experience, these short activities are designed to help you connect with yourself, your previous experiences and your hopes for future teamwork.

-

What does the word ‘team’ mean to you? Why?

-

Think of a time when you felt comfortable working with others:

- What was it that made you feel comfortable?

- Was there anything about the situation that stood out to you?

- What does this memory tell you about what you need when it comes to teamwork?

- Think of a time when you felt uncomfortable working with others:

- What was it that made you feel uncomfortable?

- Was there anything about the situation that stood out to you?

- What does this memory tell you about what you need when it comes to teamwork?

- How has this memory impacted your perception of teams and teamwork?

- Think about a behaviour that you find difficult to deal with in others:

- Why do you think you find that behaviour difficult?

- Have you had any past experiences connected to people showing such behaviour?

- What do you think you can do to better understand such behaviour?

- Think about a behaviour that you exhibit that others may find difficult to deal with.

- Why might they find it difficult to deal with such behaviour?

- What can you do to check such behaviour?

- How might people let you know that they find it difficult?

- Imagine that you are working with others to create a dream team:

- What values do you think should help guide the team?

- What do you want this team to know about you? How will you share this?

- If you had to choose three adjectives to capture your dream team, what would they be?

- Draw an image which represents this dream team.

Getting to Know One Another

If your group is new and you’re going to spend some weeks or longer working together, then spend time getting to know one another. You may want to have a meeting, or a section of every meeting, dedicated to this at the start of your team journey. This will lay a strong foundation for the work you will do regarding the remit and operation of the group, like its purpose, goals and roles, and will make your team effective at collaborating, supporting each other and establishing boundaries.

Teams need to be able to work together in adaptable and flexible ways, giving members opportunities to step outside of old habits and established comfort zones to refresh their thinking, and to create new initiatives, and solutions for emerging problems. They need to support people in taking on new responsibilities, whilst enabling them to learn. Such teamwork is vital if we are to respond to, and remain adaptable in the face of the crises we are currently facing. However, it is difficult to build teams like this and to provide the conditions in which all team members can thrive, without first understanding the strengths, vulnerabilities and aspirations of those within the teams. And for this, trust needs to be developed. This guide contains suggestions on how to create a team rooted in trust and connection.

Names

Names are fundamental to identity, to knowing one another. To help people remember each other’s names, either provide sticky labels for people to write their names on, if in person, or ask people to display the name they want to be known by on their zoom name display.

Some people have great difficulty in remembering names, or others might have the same name, so using tags can make the process easier. You might ask people to include the following alongside their name:

- Name

- Where you are from

- A personal description to add as a tag, which changes on subsequent weeks e.g. Bethan could name herself as 'Bethan Cardiff pink hair’ on week 1 and on week 2, ‘Bethan Cardiff wild pony rider’.

If you are using zoom, these are the names that will appear in the chat when people use it, so if people save chat contents at the end of the meeting, there will be distinctive reminders to help them relate comments to people.

Over time, when people know one another the names they choose to use can be playfully altered. You might for example, ask people:

- ‘If your name were to match your mood, how would you like to be known today?’

- ‘What name would you have given yourself in childhood if you had had a choice?’

- ‘What name captures the superhero within?’

Another way to help people connect through their names is by giving them the following prompts and inviting people, in turn, to share what they feel comfortable sharing:

- I was given my name because . . .

- I like / I dislike my name because . . .

- My name is / isn’t a good fit for my personality because . . .

- People assume ______ about me because of my name . . .

Check-ins and Check-outs

Check-ins and Check-outs are good opportunities for asking questions to help group members get to know one another. The types of questions that you ask in check-in may be different to those you ask in a check-out.

Check-in:

Consider asking questions that will bring the people into the present and help them process any high or lows on their minds. Most people don’t get enough attention to process these in their life, so to provide that space will help the group bond.

Consider using questions that bring out the positive and difficulties in people’s lives:

Plus:

- What’s been good since we last met?

- What’s going well in your life?

- Which three words would you use to describe good things in your life right now?

- What’s one reason for being pleased to be here today?

- What are you looking forward to in this meeting?

Minus:

- What’s been hard recently?

- What are you struggling with in life /right now?

- Which three words would you use to describe tough things in your life right now?

When a group is starting out in its first months, you may want to ask check-in questions like these in the full group. When the members of the group know one another better, these check in questions can be shared in breakout groups of 3-4 to do longer check-ins without taking up more overall time.

Ask the group if members need to know where everyone is at, or whether the group just needs time to arrive, to get into the present. If the former, then do the check in with the entire group. If the latter, then use breakout groups.

Check-out:

Focus the questions on helping people close the meeting and go back out into their lives.

Consider using one or a mix of following questions:

- What did you enjoy about today’s meeting?

- What are you taking away with you from today’s meeting (an idea, an action, some personal exploration, gratitude)?

- Who are you looking forward to being with next week, and why?

- What are you looking forward to doing next week, and why?

- What interesting challenges do you have ahead or would you like to take on?

- What will you remember to appreciate about yourself as you go about your business next week?

Icebreaker Suggestions

An icebreaker is a game that is literally used ‘to break the ice’. They can take any form, but the idea is that they all help to give each other a fuller, more rounded view of the people you’re working with. .

Curiosity Questions

- What was one of the best years in your life, and why?

- What type of foods do you like? What’s a favourite meal?

- What songs do you like, and when do you sing?

- What’s a film that you saw some time ago that had an impact on you?

- What is your favourite colour, and why?

- If you could live anywhere in the world, where would it be, and why?

- What’s a job that you’ve had that you really enjoyed, and why?

- What’s your favourite city? Use 5 words to describe it

- When did you go on a really interesting walk? Where to? What was interesting?

- What did you love to do as a ten year old?

- What’s one skill you’re good at and one skill you’d like to develop?

- What’s your favourite dance? Show us a few movements

- Who is a living person that you admire and two reasons why?

- What’s your favourite animal? Demonstrate the sounds they make

- What’s a memorable book from childhood? What enthralled you?

Games

In a virtual setting it’s very difficult to do the many kinds of physical games that are possible when people are physically together, but thinking about moving to releasing physical tensions is important for virtual meetings, and when you can combine them with something silly, they can be lighthearted and fun.

Bingo

Someone is selected to start off as the bingo caller. They think of something they’ve done recently like ‘eaten too much sugar’ (it’s got to be true of them). They ask the team - ‘Has anyone eaten too much sugar recently? ’ to raise a hand in the zoom REACT selection (bottom bar) if it’s true of them too. Notice who hasn’t raised their hand and select one of them to be the next bingo caller. If everyone lifts up their hands, then the bingo caller has another turn.

The bingo caller can ask for broad categories:

- Past experiences

- Interests

- Clothing

- Food

- Background / Family

- Dreams

Two Truths and One Lie

Everyone writes 3 statements in the chat, two of them are true and one of them is a lie. Someone keeps a tally and everyone gets to vote on which is the lie. People then reveal in turn what is the lie.

Name - Place - Animal - Thing

Someone starts and chooses the name of a river (they say e.g.Thames), the same person then allocates Place or Animal or Thing to everyone else in the team. They then must come up with a list of whatever they were allotted (Places or Animals or Things ) that begin with the letters T H A M E S. show they’ve completed with the Hand Up REACTION on screen. The person who selected the name decides when everyone has finished whether it is the first or last Hand Up that is the winner. They then ask the Winner for the name of a e.g flower. The winner then allocates Place or Animal or Thing to everyone else in the team with the letters of that flower. And so the game continues.

Designing Your Own Virtual Ice Breaker

Consider these factors before choosing your virtual ice breaker:

- Establish a purpose: Ask yourself, what ‘ice’ do you want to break? Are you simply introducing people to one another for the first time? Are you bringing people together from different parts of the neighbourhood, or people who have different cultures and backgrounds? You'll need to handle these differences sensitively and make sure that everyone can easily understand and get involved in the ice breaker.

- Define your goals and objectives: Do you want people to learn more about one another? Or is your objective more complex? For instance, do you want to encourage people to think creatively or to solve a particular problem?

- Help people feel comfortable: Your ice breaker will only be successful if everyone feels able to participate. So think about whether there are any obstacles that could hinder this, such as differences in language or culture. Steer clear of activities that might inadvertently cause offence. Bear in mind that information can often get 'lost in translation’ and that jokes and humour don't always travel well.

- Take time into account: Do you want your ice breaker to be a quick five-minute activity or something more substantial? Take into account your purpose and objectives, and whether your gathering will have people calling from different time zones.

- Choose your frequency: Do you want your ice-breaker to be a quick activity at the start of each meeting immediately after Checkin? Will you change your ice breaker every time you do it? Will the same person always take the lead or will you rotate on who gets to pick and lead the activity each meeting (if you decide on that frequency)?

- Consider technology: If doing an ice-breaker on zoom, remember that some people are "camera shy," and/or have poor internet connection or may not have the right technology. If this is the case, you might want to choose an ice-breaker that doesn't rely on people being able to see each other.

- Taking the lead: One way to get people involved is to ask them to take lead on choosing the icebreaker/checkin/checkout.

- Prepare in advance: Decide how much information you'll need to provide your participants with beforehand. Do they, for example, need to bring a prop to the meeting?

A Note on Group Size and Bonding

Group size makes a difference to bonding and building trust. Breaking into small groups is useful for people to get to know one another in more depth. Once a group has 8 people, then consider splitting it into breakout groups for some activities. This is important for people who find large groups difficult (9 is a large group for some people); sma;er groups can help people build confidence in speaking.

Dividing people into smaller groups regularly will help people to get to know each other faster, especially if the breakout groups are randomly assigned, creating different groups each time. As the group continues to meet you can vary the size of the breakout groups and make them bigger, although bigger than 5 will take up time and be more difficult for people to relate to and learn from each other.

Tips on How to Give and Receive Feedback

Being able to give and to receive feedback is important when working with others, when building relationships based on trust and honesty, and for being able to make progress – without feedback, people may be held back from reaching their full potential. Feedback, however, is not an easy thing to give and the awareness we could be upsetting someone often holds us back from sharing our ideas or feelings; it is also not an easy thing to receive – it can be hard not to take something someone has stated about you or your work personally. It is, therefore, important to focus on how we can give feedback in a constructive and compassionate way and how we can receive feedback without becoming offended. One way to start is by viewing feedback as a means of developing, of building resilience and of connecting with others.

Imagine that feedback is like having something stuck between your teeth. If no one tells you it’s there, you might spend the day wandering around and interacting with people with a piece of spinach announcing itself each time you speak. Many people may have seen it, but everyone has felt awkward enough not to say anything. Most people would rather somebody told them about the spinach. Feedback is like that. It can be difficult to say, but when shared with the right intention and the desire to help, it can be incredibly useful.

The following suggestions are designed to help facilitate the development of honest and open conversation, and the establishment of short feedback loops.

Giving Feedback

Here are some tips on how to give feedback:

- Take responsibility for what you are sharing. Make “I” statements – starting statements with“you” can sound accusatory and make people feel defensive.

- Think about your intention – why are you sharing the feedback? Is it to help someone else progress? Is it to share how you have been affected by something? Whatever your intention, want the best for the other person and for your relationship with them. Feedback is not about undermining someone or scoring a point, it is about strengthening bonds and helping people reach their highest potential self.

- Show appreciation for others if you are giving them feedback that could be received as negative – praise something that they do well. It is much easier to hear feedback if you know that you are valued.

- Give feedback in a one-on-one situation. Bringing something up in front of others can make someone feel exposed or vulnerable.

- Take it slow – if there are several things you want to mention, it is probably not worth bringing them up all at once.

- Think carefully about what you want to say – it could help you to write out your feedback before you give it and read to see how it sounds.

- Be sensitive to the fact that you are talking to someone who is as complex as you and who might have events going on in their life that you may know nothing about.

- Open the floor – see if they have feedback to offer you and ask if you could do anything differently.

Receiving Feedback

Here are some tips on how to receive feedback:

- Take responsibility for your feelings and your response. You can decide how you react in each situation.

- Try not to take the feedback personally. Assume the best of the other person – they are sharing information so that you can improve at something or so that your relationship with them can improve.

- Be aware that it is difficult to give feedback – the fact that someone is taking time to give you feedback shows that they value you and that they feel comfortable enough in your presence to do so.

- Make an effort to understand how something can be done differently – ask for support if you feel that you need it.

- Be honest – if you feel like you have been misinterpreted then say so, but do so sensitively and compassionately.

- Openly ask for feedback from others – getting into the habit of receiving feedback can be incredibly helpful for your growth and it can make receiving feedback less of a big thing.

- If some feedback has upset you, take time to process that feedback independently and think about why it has upset you. Is it related to any previous experiences? Sit with those feelings and give yourself time to work through them.

- View feedback with a growth mindset. Without feedback you might never learn things about yourself, you might not develop as much as you could. Feedback is a tool that can help you reach your potential and that can improve your relationships with others.

A Quick Guide to Holding Effective Meetings

Running meetings that keep to time, enable constructive discussion and give everyone an opportunity to have their voices heard is a difficult thing to achieve, particularly if these meetings are being held on Zoom (or any other video conferencing platform). More often than not, people talk over each other (making it impossible to hear what is being said), and meetings drag on chaotically, leaving those present tired and frustrated.

Using a set structure and hand signals to communicate, however, can resolve such communication issues and can create harmonious, inclusive and even enjoyable meetings. As can using Zoom’s breakout room capacity (if you are holding meetings online) as it enables people go off into smaller groups where they can discuss an issue in depth, before sharing their ideas with the larger group.

To have constructive, harmonious and enjoyable meetings that keep to time, it is advisable to use the following components:

- Facilitators

- Note-takers (minute-takers)

- Hand Signals

- Breakout Rooms (on Zoom)

It is also important for each person participating to trust the facilitator and to use the hand signals responsibly (please see the ‘note to participants’ section at the end of this document for more information).

The rest of this document will explain what is meant by the components listed above (the content has been adapted from Extinction Rebellion’s various People’s Assembly manuals), and is divided into the following sections for ease of reference:

Facilitators

Every meeting should have a lead facilitator, who is responsible for ensuring that the meeting runs to time and that those present are able to share their ideas without chaos breaking loose. The facilitator does not need to remain the same across consecutive meetings. Indeed, it is more effective if this responsibility is shared out and people take it in turns to take on this role each meeting.

The facilitator’s role is to look out for the hand signals, prioritising them appropriately, and to ensure inclusivity – no one person should dominate. If one person is speaking for a long time, the facilitator can request that the person rounds up, using the appropriate hand signal, or if one person repeatedly wishes to make a point, the facilitator can prioritise those requesting to speak who have not yet spoken. At the start of the meeting, the lead facilitator should request that people put themselves on mute and only unmute when they are speaking – this prevents any background noise interference and also ensures that the meeting is not interrupted with people’s exclamations or comments.

Inclusion

The facilitator should moderate participation to ensure that everyone is able to speak, should they want to. The facilitator can engage participants by inviting people to speak and by, conversely, asking people not to speak. If people have not spoken, invite them to engage with a topic by asking for their opinion. If someone has occupied a lot of the airtime, explain that you would like to ensure everyone who would like to speak is able to and/or that you are conscious of the time. Rounds can also be used: after someone has shared an idea or proposal, each person in the group can be invited to share their response and comment in turn. As can timers, so that people contribute for a set amount of time, and the round up signal is used to inform them when that time is up. These approaches can ensure that the meeting stays inclusive and can prevent some voices from dominating.

The facilitator should also be sensitive to people’s needs. Give people the opportunity to share whether or not they have specific disabilities, inviting people to do it privately should they wish to). So many disabilities are invisible, so you should never assume that people do not have them.

Using breakout rooms can help maintain inclusion as it gives people a chance to talk in smaller groups, which is particularly useful for those who are shy. If breakout groups are used, then each room needs a facilitator, who will ensure that the discussion keeps to time and that everyone is able to participate, as in the main meeting room.

Pace

The facilitator should be aware of the pace and the fact that many people will not speak English as a first language. Ask anyone speaking too quickly to repeat what they are saying or slow down, and build in time for quiet reflection. Having one minute’s silence every 20 minutes, for example, allows people to rest their minds and reflect on or process what they have heard. As can having a short 10-20 second pause after every speaker.

However, it is also the facilitator’s role to ensure that what needs to be discussed in the meeting is discussed. Suggest that times be allocated to each agenda item, and have the group prioritise items, so that the pace of the meeting is relaxed and not too rushed, with some items possibly moved to the following meeting or to be settled by email or other means outside of the meeting.

The facilitator should also be aware that people may need concentration breaks. If it feels like concentration is dipping, give people a chance to take a break, to look away from the screen, to dance together to some music, or to play a game. This can help re-energise the group.

Building Trust

Facilitators can build trust into their meetings by giving people space to check-in and check-out at the beginning and end of a meeting. These are not only great ways of entering and closing the space, they are also ways of including everybody, and giving people the chance to learn more about each other. For ideas on types of check-in, see Getting to Know One Another.

It can also be a good idea to read out a regenerative culture reminder, or some kind of statement to capture how the group present can work together, after people have checked-in, but before going through the agenda. If needed, use the example below.

A Reminder: We are transitioning to a regenerative culture. It is a culture of respect and listening, in which people arrive on time to commitments. And deal with conflicts when they arise, using short feedback loops to talk about disagreements and issues without blaming and shaming. It is a culture in which we cultivate healthy boundaries by slowing down our yeses and returning tasks when we are unable to follow through. It is a culture in which we look after ourselves and others, understanding that it is natural to make mistakes: they are a key part of the learning process and provide opportunities for growth and development. It is a healthy resilient culture built on care and support. We are all crew.

Minute-Taker / Note-Takers

The lead note-taker is responsible for keeping the minutes and recording what is being said in the main meeting. Again, unless this role is part of someone’s job description, it is good to rotate who is the note-taker, so that everyone can have an experience of fully participating in the meeting.

If breakout rooms are used, then each group should appoint a note-taker, who will record the group’s discussion and share the key findings back with the main group when the breakout rooms are closed.

Hand Signals

Point (or ‘I would like to speak’):

When someone in the group wants to say something, they should point their index finger up and wait for the facilitator to let them have their turn in speaking. It is vital that people do not talk over anyone else and wait for their turn. If someone, who has not yet said anything, puts their finger up to speak, whilst others have spoken a lot, then the facilitator should give that person priority over the 'stack' (the queue or order of speakers based on the order they raised their finger to speak).

Direct Point:

If someone has directly relevant information to what is being said, then they can make the 'direct point' hand signal and the facilitator will let them provide that information immediately after the person speaking has finished. Think of the direct point hand signal as being like brackets, which are used to add critical information that a speaker is not aware of e.g. “the meeting has now been changed to Wednesday”. The direct point signal is not an excuse to jump the queue just to make a point. It is important that people do not abuse this signal as otherwise it can make all present lose trust in the process.

Wavy Hands (I Agree):

The 'wavy hands' signal of approval is used to show agreement or support for something someone has said. It instantly indicates how much consensus there is towards something and can highlight how popular an idea is. If everybody erupts into a forest of waving hands during a breakout session, for example, the note taker can see that this is one of the more popular points made and it will become one of the key bullet points fed back to the main meeting room.

Clarification:

If someone says something that is unclear, people can hold their hand in a ‘C’ shape as the 'clarification' signal. The facilitator will then pause the discussion giving the person who made the signal the opportunity to ask a question to clear up any confusion. This signal should be given priority above all others as it means that someone does not understand something and it may thus inhibit their ability to engage in the discussion.

Technical point:

If someone has information that is immediately relevant to the running of the meeting, they make a 'technical point' signal by making a ‘T’ shape with their hands. This is only to be used for concerns external to the discussion that need to be addressed immediately e.g. “We only have ten minutes of this meeting left” or “I am the note taker and I need the loo so can someone else take over?” The facilitator should stop the discussion to address the technical point.

Round Up:

Facilitators need to ensure that no one speaks for more than necessary (two minutes is a suggested maximum amount of time as it encourages people to be concise). If someone has been speaking for two minutes (or whatever the set amount of time is), the facilitator makes the ‘round up’ hand signal by repeatedly making a circular motion with their hands (as if they are tracing a ball). This must be done sensitively, but firmly as it ensures that no one person dominates the meeting.

Speak up:

If someone is speaking too quietly or they cannot be heard, others can ask them to raise their voice by raising and lowering their hands with palms open and facing up.

Break Out Rooms

To brainstorm ideas or discuss a subject in depth, use the breakout room feature on Zoom, as it will give people space to discuss their ideas in smaller groups. Please note, breakout rooms can only be created by the person who is logged in as the host (though the host can transfer hosting to another person, if desired).

Whoever is the host must look at the control panel at the bottom of the screen for the button stating Breakout Rooms.

The host should divide the number of participants in total by the number of people wanted in each group, and Zoom will automatically assign people to rooms. Once they have done this, they can look at the lists to check that all rooms have the right number of people.

If certain people need to work together, the host can manually assign people to rooms.

The host can also set the options, such as timings, for the breakout rooms (see the example outline below), and can communicate with all the breakout rooms by using the broadcast button to send messages about timing or other important points to consider.

For each breakout room to run effectively, it will need a facilitator and a note-taker. The note-taker should be responsible for feeding the key ideas back to the rest of the group. If there are several breakout groups then consider having a limited number of ideas to feedback to ensure the meeting keeps to time e.g. each group might be asked to choose three key ideas for their note-taker to feedback.

Note to Participants

You are each responsible for creating a considerate space in which everyone is able to participate. It is, therefore, important to reflect on your own involvement in the meeting.

To create a constructive, harmonious and engaging meeting environment, consider the following points:

- Mute yourself when you are not speaking as it ensures that you don’t distract attention away from the speaker.

- Respect the facilitator’s role to hold the meeting and to intervene to give everyone a fair chance to speak; it is likely there won’t be time for everyone to say everything they want to say, so please allow space to make sure others are heard too.

- Please think before you speak and consider whether what you are saying is vital or not. Ask yourself: “Why am I talking? Do I really need to add my view in here? Is what I am saying necessary, or do I just want to speak?” You don’t need to repeat what someone else has said, that’s what the jazz hands are for.

- If someone has said your point, put your hand down so the facilitator knows that you are giving up your place in the queue stack, otherwise keep it up.

- Let someone who hasn’t spoken in awhile go ahead of you. So when it’s your turn, say “X hasn’t spoken in a while, take their point ahead of mine”.

Building Healthy & Empowered Teams

Introduction

This workshop and guide were developed because “there's no such thing as a structureless group”, as explained by Jo Freeman in her text, The Tyranny of Structureless. Often people think that when there is no explicit power structure or hierarchy, that everyone is equal. However, this is not the case. There are always implicit power dynamics at play. The vast majority of people have grown up in hierarchical societies from family, to family, to workplaces, there’s someone in charge and someone who has to listen to them. These are explicit hierarchies. But there are also implicit hierarchies, such as the cool kids at school who call the shots and get the back seat of the bus. Those kids don’t have any official titles that give them that power, they have it because others want to be seen and liked by them. This is one example, but implicit power can mean an advantage for one person over another due to their sex, age, race, class, abilities, etc. These injustices are present in society and will be present in our team unless we do something about it. By proactively deciding how we organise, we can reflect our values and leave behind ways of working that reproduce the injustices in society.

Building teams is an important part of community building because just as you want a good culture in the community, it grows from the people who are organising and how they relate to each other. When we build a team, the culture we create sets the tone for the community project that grows from it. Do you want the culture to be one where everyone turns to you and is lost without you? Or one where people are willing to step up and use their own judgement, especially when you need to take a break from the project?

Trust is essential to working as a team. By having a clear structure of how you organise, you can be clear about what to expect from each other and where your boundaries lie. This will enable you to build trust which is essential for a healthy, productive team and in order to create an experimental culture. See more on Building a Culture of Trust & Support.

Most importantly, teams stick together when the going gets tough because people don’t want to bail on their friends. Generally, people join community projects and activist groups because they are interested in the activities or they want to change their community or world. However, people stay for friendship. These means teams in volunteer contexts should make room for getting to know each other and having a laugh outside of a meeting context. Cups of tea at each other’s house, potluck dinners, pints in the beer garden, or just spending part of the meeting chatting is an important part of being a team and should not be underestimated.

What is a team?

A team is a group of people who are dependent on each other in order to achieve a shared purpose. Creating a team is important because otherwise you’re a random bunch of people pulling in different directions and prone to distrust. A team has a sense of unity in achieving their shared purpose and they collaborate and support each other

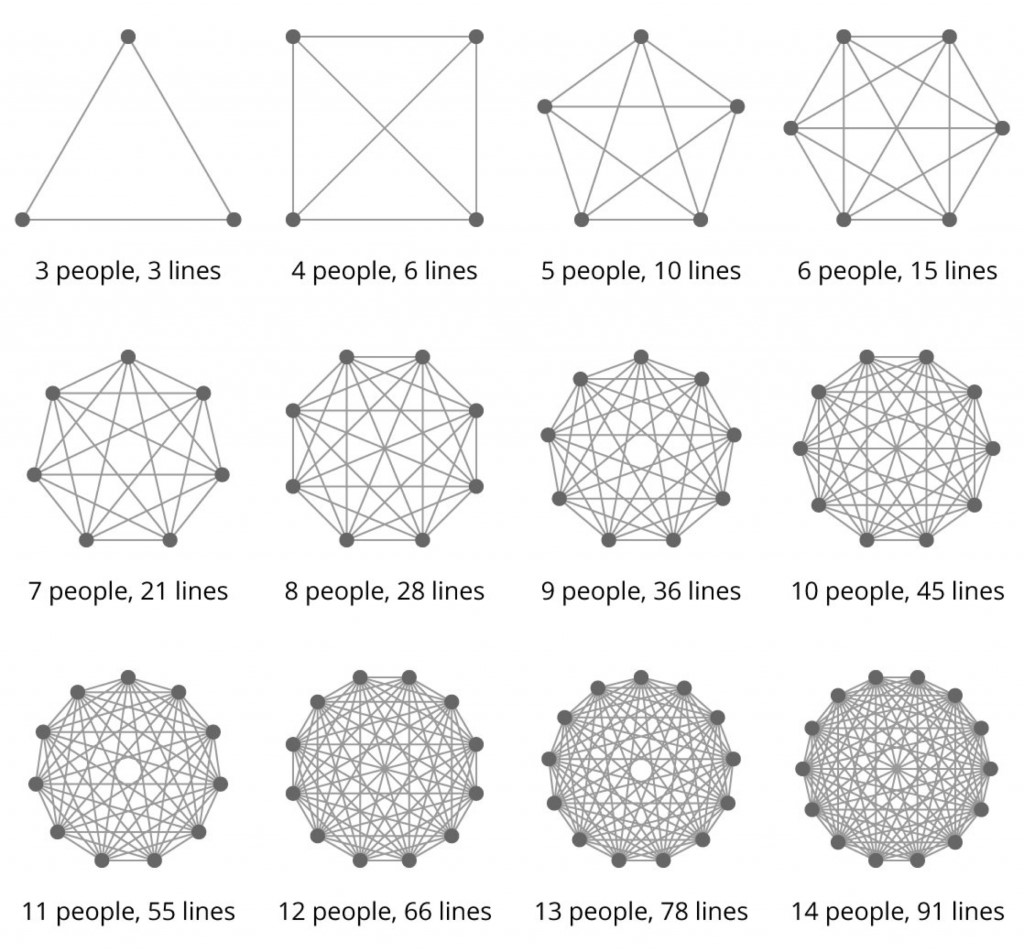

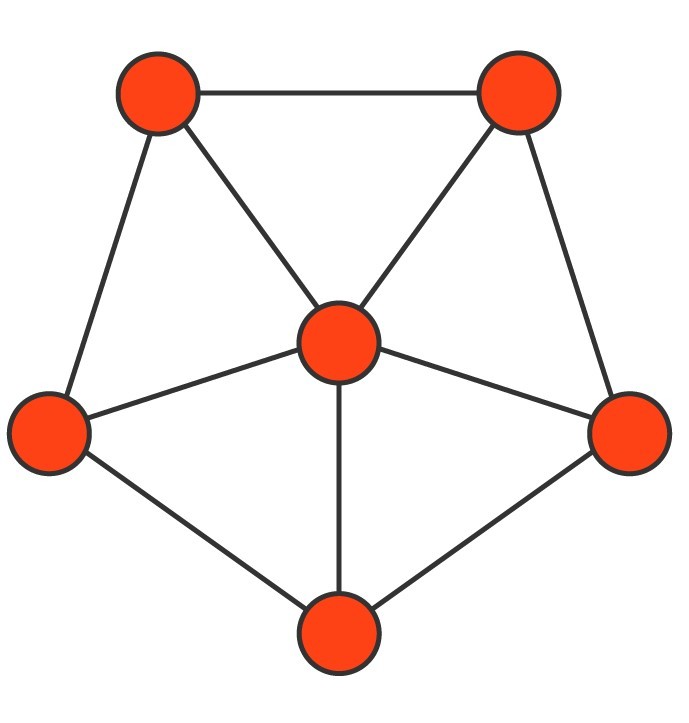

We recommend a team is a maximum of 6 - 8 people. Why not more than 8 people? Because as you can see in this picture, the number of connections you have to maintain dramatically increases after 6 - 8 people. 6 - 8 is manageable. After 8 your team can create subteams, e.g., one person working on the newsletter, then it expands to 2 and then maybe 3.

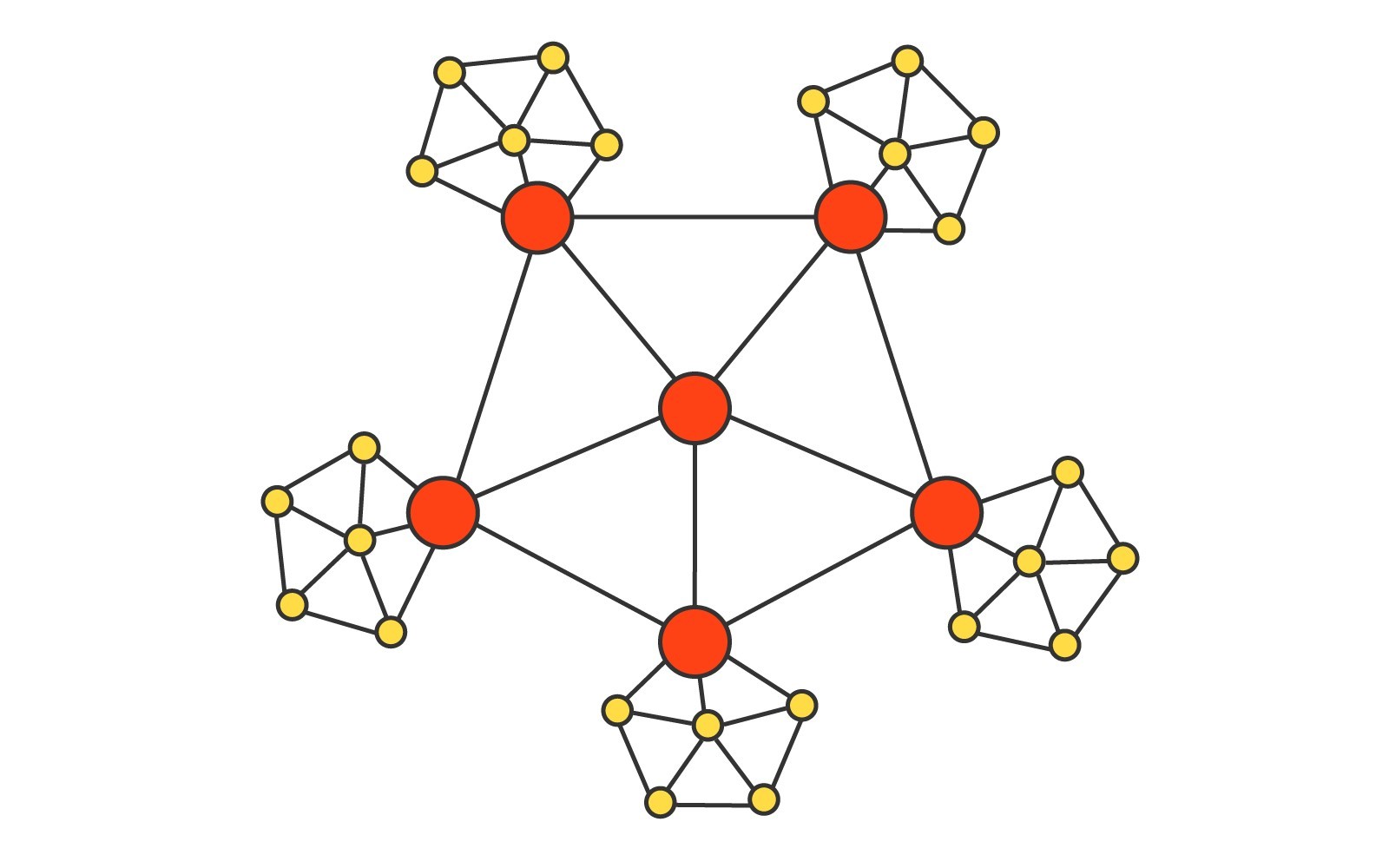

When the team becomes more than 8 people, you may want to start thinking about creating off-shoot teams, as shown in the diagram below.

Image reference: Act, Build, Change

Image reference: Act, Build, Change

What makes a good team?

There are 5 key elements that make up a good team:

Feeling safe (Trust)

This is by far the most important. It determines how easily members can take risks, make mistakes and ask for help without fear of retribution from the rest of the team.

Dependability

Effective teams are ones where members can rely on each other to deliver work when agreed.

Structure & Clarity

How are decisions made? Who is doing which role? Do I know exactly how our work is structured?

Meaning

Is the work personally meaningful to people in the team?

Impact

Do people feel like their contribution is having a significant impact on the overall purpose of the team or organisation?

Here are some questions you can ask yourself as a team:

- Can we, as a team, take a risk without feeling insecure or embarrassed?

- Can we count on each other to deliver high-quality results on time?

- Are our goals, roles, and execution plans clear?

- Are we working on something that is personally meaningful to each of us?

- Do we fundamentally believe that the work that we’re doing matters?

Volunteer team structures

Team structure matters more than the amount of free-time people have to give:

- If teams are interdependent, it encourages people to get shit done as people are waiting for them

- Equal division of labour encourages people to give more time. We need equal workloads in teams - more important than free time.

- Spending less time in meetings! Do meetings for relationship building or coordination, not doing the actual work. Less time in collective meetings.

The difference is 4 hours/volunteer/month vs 40 hours! 10x difference. Also, people who receive more training are more committed time-wise.

What do we want to do?

Shared Purpose

Teams need a purpose that engages their commitment and orients them in a shared direction. They need something that gives them meaning and to work towards! The purpose needs to be shared because it needs to be something that each person buys into — that’s why it can be really useful to create the purpose together.

Teams should have 3 elements in a shared purpose:

- Clear: What exactly are we trying to achieve?

- Challenging: A challenge can be motivating and can encourage dreaming big.

- Consequential: Where does it fit into the bigger picture? A shared purpose in a volunteer team should tie back to how it fits into the overall purpose of the organisation or the wider group you’re working with.

How to create a shared purpose

What do we want to achieve? What does the world look like when your team has finished their work? This should be written like the outcome you want to see, e.g., complete the sentence… ‘If our team fulfilled its purpose, there would be…’ or ‘We imagine a world where…’. For example, if your team If the Aylesbury ‘Reclaiming your Local Council’ team fulfilled its purpose, there would be participatory democracy at the local council level, independent of party politics. A useful facilitation tool for helping a team to create a shared purpose is pyramiding.

- Solo reflection: Everyone writes down their understanding of the team’s purpose - 5 mins

- Pair share: Share your statement with another person & combine - 15 mins

- Pair the pairs: Each pair shares and combines their statement with another pair - 15 mins

- Each group shares with the whole group - 10 mins

- Create one statement that captures the all key points - 15 mins

If one statement cannot be reached within the meeting time. You can ask one person to take the final statement from each of the groups and then present it to the team at the next meeting. The team can then decide whether this reflects their shared purpose and adjust it as necessary.

Projects

What projects do we need to reach to achieve our purpose?

Now let’s consider what we need to do to achieve our purpose: what milestones do we want to set? Projects & milestones are important to set out as it provides valuable evidence of when a team is making progress towards their purpose. When projects are completed and milestones achieved, teams should celebrate each other for making meaningful progress! Celebrating others and recognising achievement is an important part of building a healthy culture of trust & support.

First, we’re going to do some divergent thinking. That means thinking about all the possible things we could do or goals we could set. Then we’ll narrow it down with some convergent thinking.

Divergent Thinking - 12 mins

- Solo brainstorm all goals on post-its - 7 mins

- Write down the opposite of a goal you’d want to set - 5 mins

- Then try switch that opposite-goal to something positive, a goal you would want to set - 5 mins

Convergent Thinking

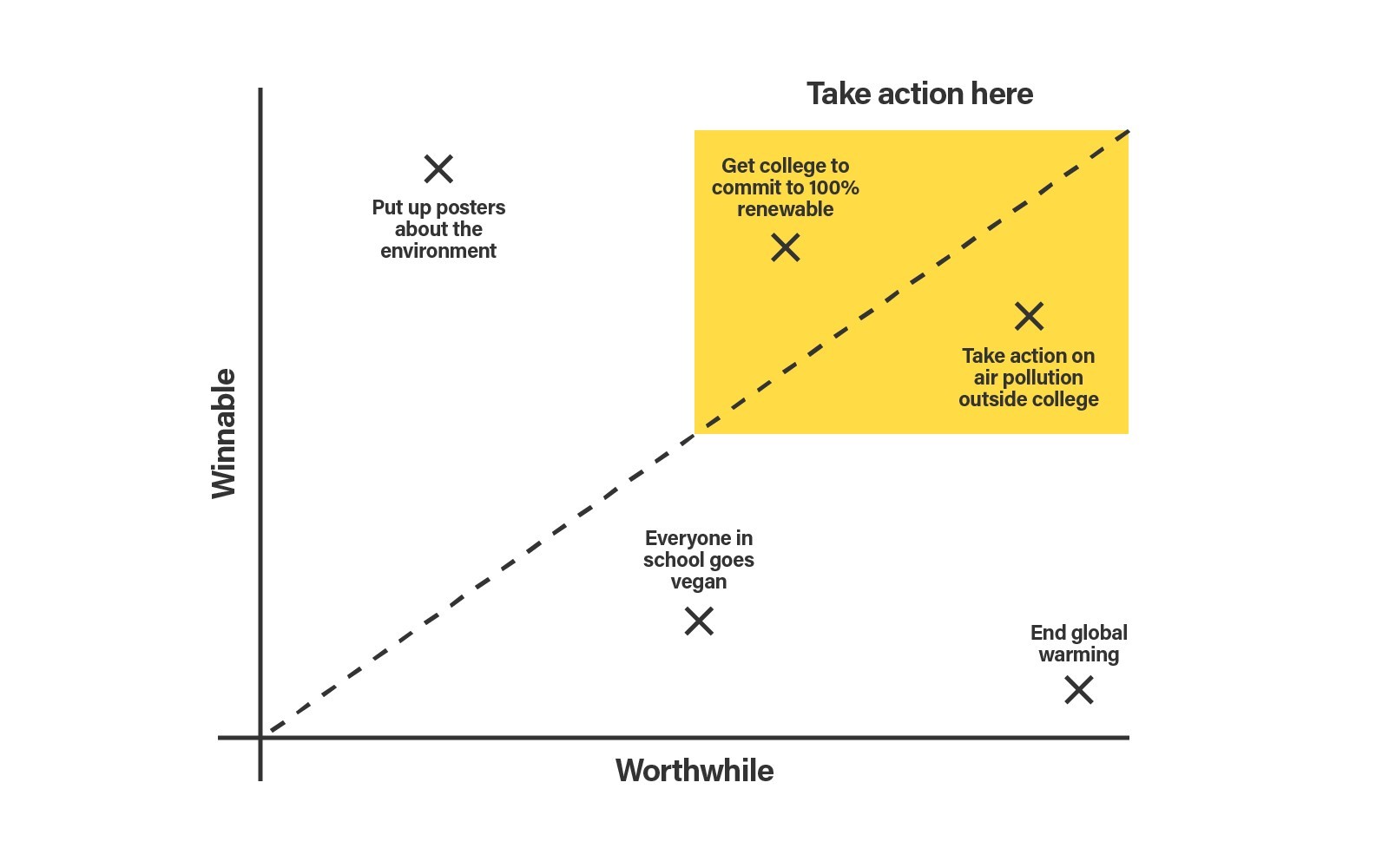

- Map them on scale of winnable (achievable) and worthwhile (impactful)

- Consider whether it’s better that some happen before others (maybe number the order they need to happen in)

- Consider which ones would be the most enjoyable to do, that suit your interests best

- On the basis of either of the previous criteria, prioritise which one you’re team will work towards first

Then take those one or two milestones you want to work towards. Brainstorm how you would achieve them- what steps and activities need to be taken in order to achieve that milestone. If you discover that one isn’t so feasible, then you can pick another milestone.

Roles

Why do we need roles?

We need roles because it’s really useful to:

- Know what decisions you can make without having to check with others

- Have someone bottomlining a task or set of tasks/activities

- (that means one person is going to make sure it gets done, not that they have to do it themselves and that no one else can do it)

- Know who to talk to about specific activities

What roles do we need?

So you’ve talked about the milestones your team needs to achieve and some activities to get there. Now let’s group those activities into roles. Roles should be based on outcomes you want to achieve, e.g., finding a venue for a fundraiser.

There may be some roles that will need to be done on an ongoing and relevant to the team generally (e.g., newsletter writer). And there may be other roles that will be project based (finding a venue for the fundraiser).

- Brainstorm all the tasks or activities that need to be done to achieve your milestones or in a project.

- Group the tasks you think make sense together.

- Discuss any disagreements.

- Decide on the wording of the roles… (more on decision making later).

Nominating people to roles

This is an alternative to a more formal process outlined here. Given the activities we’ve outlined, what roles do people see for themselves? What interests align with the activities we’ve prioritised? Do a ‘go-around’ which is where everyone in the team gets a chance to speak.

This may not be the most speedy way to decide roles, but it’s important to get to know each other. You can either let people speak freely or time each other so that everyone has 3 minutes each, for example.

Each person states...

- What tasks they like doing, what gives them energy

- The role/area that they’re interested in

- Their level of commitment in terms of hours of week and whether they have other projects on the go

It’s perfectly fine to share roles if that suits best. You can withdraw your consent and make changes to these at any time, so go with something that’s good enough to try and make changes later. This allows you to make decisions and move forwards and change things when you have more info based on your experience.

The Dark Side of Roles

Roles can tend to emphasise an individualistic perspective, which undermines team effort. They can lead to team mates focusing on their role (I’m just doing what's in my mandate), above achieving the purpose of the team. Individual roles become more salient because they're written down. This could be counteracted by consenting to group agreements which emphasise the team’s cultural values.

More important than roles are projects. Projects within a team can be a group of 2 - 4 people working on a specific task or towards a specific goal. Project teams are small enough that roles are not as important and people can keep track of who’s doing what within the team. Projects like this can feel more collaborative than the idea of roles.

Roles can be good for clarity of who is doing what and structure of teams. This clarity means psychological safety!

How do we want to work together?

This section is about helping your team figure out how you want to communicate, make decisions, and give feedback and set boundaries.

Decision Making

Why should we decide how to make decisions?

A mutually agreed decision making process creates clarity and clarity can prevent some types of conflict. People need to know that proposals and ideas they bring forward are going to be handled in a fair & democratic way. This encourages people to bring more ideas and take risks when they are confident the group will respect an agreed decision-making process. (They feel their ideas will be assessed on its merits rather than them having to fight for space to be heard in the group). And so a clear decision making process can help to create psychological safety amongst team members. Also, having a say in how the team functions is empowering - it models the democracy we want to see.

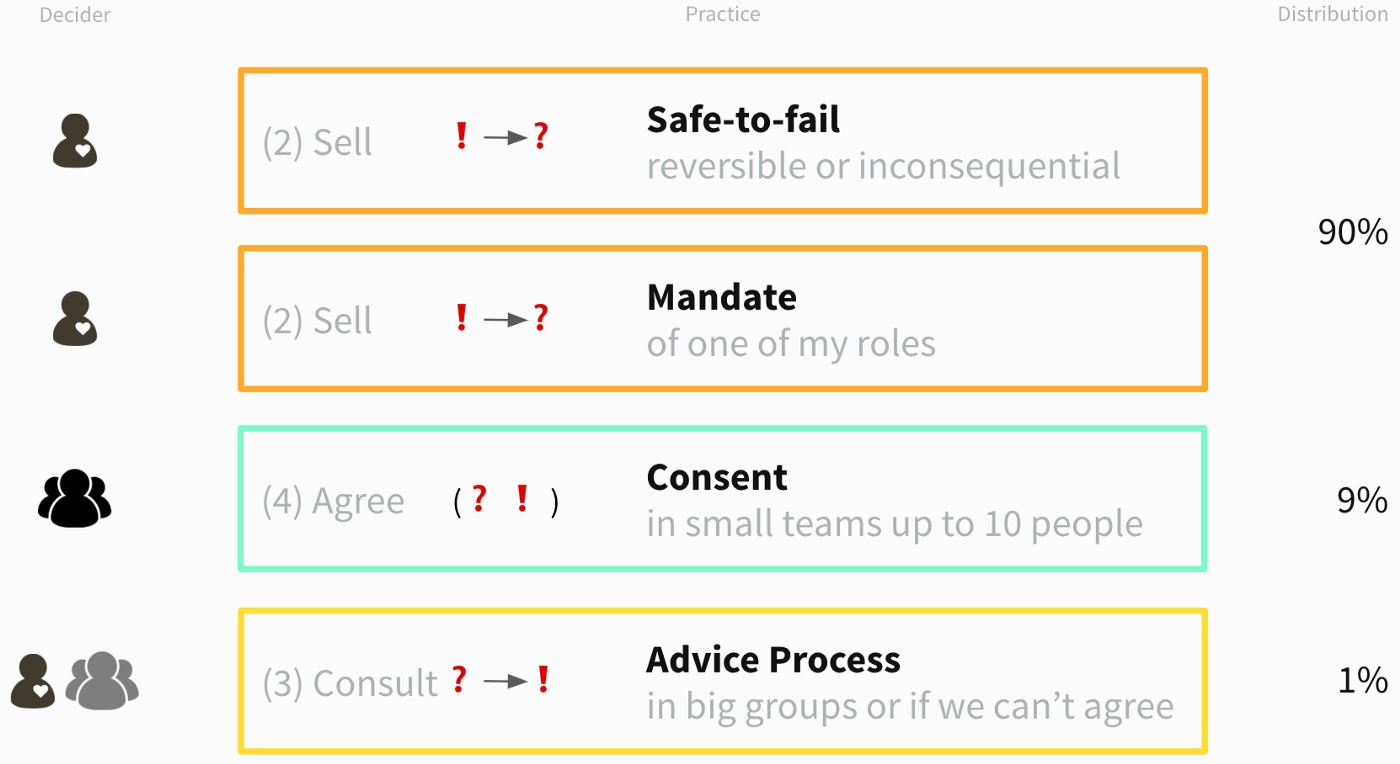

Group vs Role Decisions

Group decisions are great to get input from everyone. But they can take a long time so we suggest you only do them when necessary. Most decisions should be made by someone in a role. If a decision is recurring delegate it to a role by adding it to an existing one or creating a new role.

People can still input into a decision if the role holder uses the advice process. This is where you ask advice from those most affected by the decision and/or those with expertise (including lived experience). The role holder doesn’t have to follow the advice, they consider it and weigh it against all considerations.

Who should make decisions when?

One guideline of how often to use each process can be seen below:

- 90% of decisions made by individuals from their role (smaller & reversible decisions).

- 9% by a group decision making process (e.g. consent) when a decision is more important)

- 1% by individuals deciding for groups (advice process when a group can’t decide).

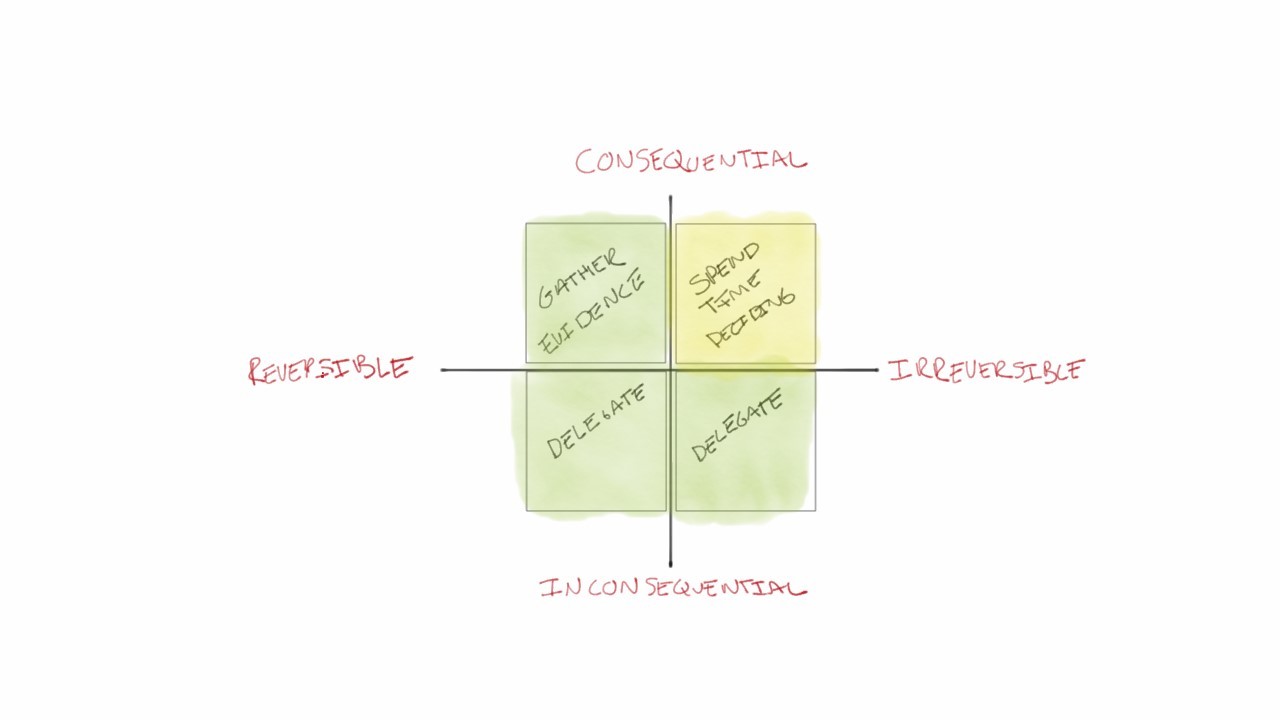

Individuals: If a decision has a smaller impact or can be corrected easily, that is an indicator that an individual could make it alone. An example of this would be writing a single social media post for a shared page (as each individual social media post isn’t that important).

Group: For more important and irreversible decisions, that is a time to seek consent from the group rather than deciding individually. An example of this might be moving office. Moving office would have quite a large impact and is largely irreversible so it’s best to seek consent from the group before deciding this yourself!

Individuals deciding for groups: If the group cannot reach consent, then it is best the group delegates and trusts one person to make the decision, who has the responsibility to consult the relevant people and gather advice before doing so. For example, when the group cannot decide who goes to meet the local councillor, you could pick one person who takes all of the considerations (what is the meeting about, who has knowledge in that area) into account and accept whatever decision they make.

Teams can decide what decisions they’re happy for team members to make themselves, and what ones they want to make as a group.

Group Decision Making Processes

There are many ways to make decisions and many different types of decisions. Here are some different decision making processes:

- Informal consensus: This is a very common approach to decision making. It happens when someone presents an idea and no decision making process is explicitly made clear, but it is assumed that everyone must agree with the idea and so there is a pressure to conform.

- Formal consensus: In consensus based decision making, the group is asked “Do you agree with this proposal? Do you approve?” Though not everyone needs to agree with the proposal, it can make work slow as not everyone might agree.

- Majority vote: everyone can vote for one option and the option with over 51% wins. You can also have a supermajority of 60% or 80% (this level would be decided beforehand).

- Consent: In consent-based decision making, the group is asked “Is this safe enough to try or will this proposal cause harm?” This allows the group to improve the proposal so that it doesn’t cause harm, but means we don’t have to wait till proposals are perfect, we can try things out and adjust or stop if it’s not working well. It’s easier to find something that everyone can tolerate, rather than something everyone loves.

There are many more decision making processes. The Decider app helps you determine what decision method suits the decision you’re trying to make. All of these methods have pros and cons which you can see if you click on the buttons at the bottom of the Decider app homepage. Next, we will describe consent based decision making in more detail, since it’s the process we recommend.

Consent Based Decision Making

A key thing about consent is that it can be withdrawn at any time. You would then bring a new proposal and bring it to the weekly meeting.

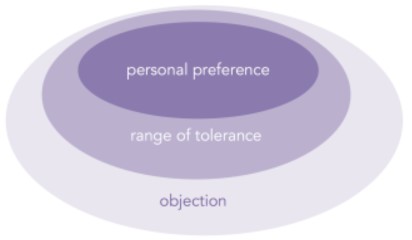

3 Levels of agreement:

- Support: Enthusiastic to lukewarm support

- Support with concerns: Would like to share some concerns but OK with proposal going ahead

- Objection: Veto the proposal going ahead until the proposal is changed

Objections:

- Objections must be principled or grounded in evidence, rather than a personal opinion or preference.

- Concerns (e.g., this proposal is incomplete) need to be addressed but are not a reason to stop the proposal going ahead.

- We pass a proposal when it’s safe enough to try, not perfect.

- Objections should be welcome because addressing them will make the proposal stronger.

Whatever decision making process you decide to use in your team, it’s important that you DO decide on one. Not having a clear decision making process can lead to stagnation. Consent allows you to try things and change them when they don’t work - this keeps us experimenting.

Sample Decision Making Agreements

- We want to make decisions in a way that is inclusive and effective.

- We use group decision making when it’s important to do so, not by default.

- If a decision is recurring, we delegate it to someone in a role unless it’s important that that decision is made by the team.

- We use consent based decision making for group decisions. We recognise that consent can be withdrawn at any time (and the person withdrawing consent is encouraged to bring a new proposal).

- We pass a proposal when it’s safe enough to try, not perfect.

- Someone making a decision seeks the advice of those affected by the decision beforehand. They take the advice into consideration, but do not have to follow it.

- If a decision creates greater workload, the decision is made by the person who would take on that workload.

How to decide how to decide?

You can use the most inclusive decision making method to make the decision to use a different method. For example, the team could use formal consensus to agree on the decision making agreements (which could include consent based decision making which would be used from then on).

Group Agreements

Why do we need group agreements?

Group agreements are about understanding each other’s values around working, how you’d like to work together as a team and agreeing on things you can hold each other to. Group agreements are about understanding each other’s values around working, how you’d like to work together as a team and agreeing on things you can hold each other to. This is extremely important in building a healthy culture of psychological safety within teams, as now each person knows what other people in the team cares about. Psychological safety and trust are some of the most important things in determining the effectiveness in a team.

There are many different types of group agreements we’re going to talk about here, e.g., ones around decision making to guidelines for meetings and giving feedback.

You don’t have to decide all group agreements within the same meeting. They can be spaced out, but it’s better to do them sooner rather than later because group agreements help set up the culture and help you keep each other to account. You can also copy the sample group agreement we have here and then change them as the need arises.

Brainstorming Your Agreements

Now let’s make some group agreements and agree to them! Use the pyradming process described above to ask the team…

- What’s important to you about decision making? What agreements around decision making would you need to make this team a safe and respectful place for us to work in?

- Try to make them practical.

- Take for example "it's alright to disagree" - how would this work practically? You could add "... by challenging what a person says, not talking the person themselves."

- Another example is Confidentiality. This is also quite vague and you will need to discuss what people understand by it and what level of confidentiality they expect from the group.

- Solo: reflect on the question and write out your ideas for agreements

- Pairs: people get into pairs and combine any similar proposed agreements

- Round: As a group, each person shares what’s important to them and not to repeat any that have already been mentioned (Arrange them into clusters of post-its on the wall if possible)

- This should be captured in a place everyone can see.

Consenting to Your Agreements

After you’ve captured each of the agreements somewhere everyone can see, you’re ready to use consent based decision making! Here are a series of steps… Remember they don’t have to be perfect, you can change and update them at any time.

- Questions Round: anyone can ask questions to make sure they understand what the proposed agreement means

- Reaction Round: everyone gets an opportunity to say whether they have concerns (whether they are quite mild or very serious ones that would prevent them from supporting the proposal)

- It’s ok to be indifferent to some of the proposed agreements, they should be included if they’re important to someone.

- Controversial agreements could be taken out at this time, and rephrased/worked on by those with strong opinions and then proposed as an additional agreement at the next meeting.

- Consent round: each person states whether they support the proposal or object to it. If there’s an objection, ask the person to explain more. If the objection is valid (see above), amend the proposal until there are no more objections.

It’s important to explain the process to your team before diving in and to be strict with keeping them to questions during the question round. Otherwise, some people will start reacting when they may not fully understand the proposal which causes a lot of confusion. When new people join the team, they are asked to read the group agreements and consent to them.

Feedback

How to give feedback?

It’s important to have a way of addressing issues if something isn’t working. We encourage you to be open and honest about when something isn’t working for you by giving feedback. Honesty is essential for building trust, and trust is essential for healthy teams.

Feedback is a really important part of organising as a volunteer team where no one person is in charge. It will help the team work better or help you participate more fully, or both, so we can think of it like a gift to the team. The purpose of feedback is to help each other reach their full potential and also to help us as a group to move towards our shared purpose. It’s important to note that you should give positive feedback when things are working well. This helps build trust within the team and lets people know they are appreciated. It makes it so much easier to give other feedback later on so it is not just a tool when things are going wrong!

What to give feedback on?

Feedback can be useful when you feel a difference between how things currently are and a better way in which things could be.

Feedback can be about small things that your team mates might do that piss you off, little things you appreciate or major things about the direction of the team’s work. We want to encourage a culture of valuing each other, raising concerns and being honest, so we can work together as best we can.

Example: I want to chat about people arriving late for meetings. I make an effort to arrive on time for commitments and I feel disappointed & let-down when people arrive late. It means we get less done overall and this work is something I really care about and is close to my heart. My request is that people arrive a few minutes early for a meeting so we can start on time and even have a social chat beforehand!

When to give feedback?

We suggest that feedback is welcome at any meeting. If the feedback is primarily relevant to one person, we suggest you share it with them outside of the meeting. If it’s relevant to the whole group, the weekly meeting is the most appropriate place to share it.

Giving feedback to a team/in a meeting:

The person describes their feedback and if they have an idea on how to resolve it, they write it down as a proposal or they share it with their teammates ahead of the meeting. (Remember not all work has to happen in the meeting, the more that can happen outside of it, the better.) If the person with the feedback doesn’t know how to resolve it, the team could try to work it out together in the meeting, or a small group could work on it outside the meeting and make a proposal for the following week.

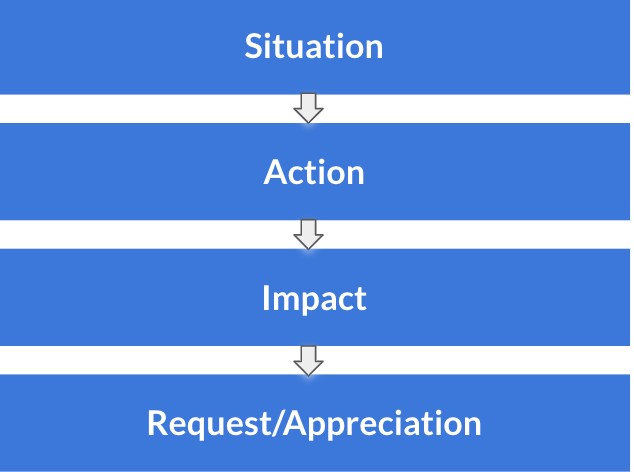

Framework for giving feedback to an individual:

- Situation: What was the context? Be specific of where and when

- Action: What specific action or behaviour did you observe? Don’t interpret their actions or make assumptions of their motives.

- Impact: What was the impact of their actions? How did it make you feel? Do they understand/see that?

- Request/Appreciation: State requests for future behaviour or express appreciation if positive.

Tips for giving feedback:

- What is the intention? Is it to help someone else progress? Is it to share how you have been affected by something? Whatever your intention, it should be to support the other person and for your relationship with them.

- Timely: Give the feedback as soon as possible after the situation. But it’s best to wait until any emotional energy has settled down so that you can give the feedback in a calm, clear-headed way.

- Is this the right time? Ask the person whether they are able to hear some feedback from you at that time? They may be having a difficult day and it may be better to rearrange another time to speak.

- Give it in private: Bringing something up in front of others can make someone feel exposed or vulnerable. Give feedback in private if possible.

- Why it matters: Explain why it’s important to you or the team. People will be more willing to engage if they understand where it’s coming from.

- Be specific: What exactly are you giving feedback on and can you provide an example of the behaviour?

- Avoid making assumptions: Avoid interpreting someone’s behaviour and guessing their motives. It’s best to ask questions and inquire what their motives/intentions were.

- Double check: Make sure the person you’re giving feedback to has understood your concerns. Ask them to summarise what they heard or ask open questions.

- Openness to dialogue: Be open to hearing the person’s side of the story and listen to their needs so they feel their wellbeing matters. Action plan: Develop an action plan going forward, so that both parties can move forward together.

- Vocab: Avoid words like “always” and “never”

Tips for receiving feedback:

- Be receptive and listen. You may want to clarify your intentions or something that you did, but try not to jump to defending yourself.

- Trust in the person giving you feedback: They are sharing something that is important to them, and may be useful to help you grow as a person or for your relationship to grow.

- Clarify: Make sure you have understood fully by repeating back and checking you’ve understood what they are saying.

- This is an opportunity for growth! Ask for suggestions and how to improve.

Resources for reading more about feedback: Tips on How to Give and Receive Feedback

Use the Consenting to Your Agreements process above to help your team decide what’s important to them about giving feedback. Here are some sample agreements that include giving feedback, meetings and general ways of working.

Sample Group Agreements for Meetings & General Ways of Working

- Everyone is able to contribute

- more talkative people: show a little restraint

- quieter people: your contributions are very welcome

- Only one person speaks at a time

- put up your hand if you want to speak and wait for your turn

- Respect each others' opinions, especially if you don't agree with them

- Confidentiality - personal details and stories should not be repeated outside of the space in which they were shared without permission

- Be conscious of time - help stick to it, or negotiate for more (e.g., we’ve given 15 minutes for this decision but ...)

- Mobile phones off to minimise disruptions

- Regular breaks - acknowledge that concentrating for long periods of time is difficult

- Communicate via email or Mattermost (Whatsapp is only for very urgent things)

- Respect that the facilitator may need to interrupt at times

- We acknowledge when we have broken a commitment (this prevents a culture of in which breaking commitments is normal)

- Feedback is welcome because we recognise that processing tensions is part of becoming a healthy team and keeping team mates fully engaged.

- When someone brings a tension, we collectively take it on and try to resolve it.

How to help your team along

Leadership

What do you think of when you think of a leader? Who do you imagine? Usually we think of leaders as someone, usually a man, a CEO type figure, who has a vision and tells people what to do and lead s the team to victory. This is one style of leadership - a style that will probably not be that helpful if you want a team that can manage itself, a team where anyone can step up when they see the need for something to be done - a collaborative team.

There are many different styles of leadership, such as visionary, mentoring, facilitation and thought leadership. We’re going to focus on facilitation leadership because it is the most appropriate approach when creating an empowered team. Facilitation leadership is helping the team achieve their purpose and ensuring everyone can contribute so the team can harness its collective wisdom.

Different styles of leadership may be useful for different aspects of a team. For example, someone may have an idea for a specific action that they take the lead on organising in a more traditional way. But generally, we recommend facilitative leadership for helping the team achieve it’s shared purpose.

There are many different types of facilitation as there are different types of leadership, for example, some facilitators just prefer to be the referee and help the team stick to the agreed process. However, facilitation can also be more than keeping track of the order in which people have their hand up! Facilitators can set the tone of a meeting and so influence the culture.

The purpose of facilitation is to help the group move towards their shared purpose. A facilitator is there to ensure that everyone in the group has equal opportunities to bring their individual gifts to the table, which in turn makes the whole group better off. Good facilitation helps us harness the collective wisdom of the entire group, by making sure that everyone participates fully & equitably in the group environment.

Facilitative Leadership Skills

Here are some key skills for facilitative leaders that spell CARES:

C: Celebrate people's contributions and achievements!

A: Aligned with the purpose

R: Encouraging taking action points/responsibility

E: Creating an environment in which everyone can contribute fully

S: Synthesising what’s being said & making requests explicit. Sometimes people don’t

Rotate the facilitator and the leader

People learn by doing and so there’s no better way to become a good facilitator than trying it out. Encourage your teammates to give it a go and let them find their own way even if it’s not how you would do it. Check out the feedback section to learn more about how to ask if people want feedback and then give good feedback.

Facilitative leadership can be done separate from facilitating a meeting. People often assume there can only be one leader, however, teams can be leaderful. That means anyone can step up when they see the need for leadership. Explicitly changing the leader can also be really useful. Being a leader can be tiring, so just as geese flying in a V rotate the leader, empowered teams should too.

Facilitation Leadership Resources

Facilitation as a Leadership Style

Facilitation is a Leadership Skill

The Art of Facilitative Leadership

General Facilitation Resources Meeting structure A Quick Guide to Holding Effective Meetings

Facilitation Tools

Here are some different ways of running a meeting that can help your teammates contribute to the fullest. Some processes can draw people out and make the task a lot more fun.

Process Tools

- 1,2,4 all

- Described above

- Pair Share

- People pair up and share their thoughts, feelings and stories. This can be very useful after some solo reflection time.

- Negative Brainstorm

- Take the question you want answered and flip it so it is framed negatively. For example, if I want to know ‘how can we build trust in our team?’ I could turn that question into ‘how can we build mistrust/destroy trust in our team?’

- Spend some time brainstorming around this question

- Then take each of those suggestions, e.g., ‘insult each other every time we see each other’ and flip it again, e.g., ‘compliment each other every time we see each other’.

- It’s a really fun technique that gets a few laughs and helps people think more freely.

- Double diamond

- Starhawk visioning:

- imagine your perfect world, how do people communicate, what does it look/smell like, what are the group norms? Can be a prelude to brainstorming. Put top 3 on post-its.

- Appreciative enquiry:

- Think back to when you were in a good team, how many people, what about that team was good? How did you meet? What did you do? What were the norms? How did make decisions? How often did you meet? What was the gender balance? Feel like you have autonomy?

- Turn-based contribution:

- Ask a question & people solo brainstorm

- Pick 3 people at random

- Ask a different question & people solo brainstorm

- Then pick a new

- Ask a different question & people solo brainstorm

- Then another 3

- So everyone gets a chance to speak. Works for related questions, each with multiple answers.

- Use post it notes & stars from Training for Change

Tools: (e.g., double diamond, need lots of different methods for different things )

- Pyramiding:

- Pyramiding is a common technique used to avoid anchoring. Anchoring is the process when one person’s idea can cause the rest of the group to become “anchored” on that particular proposal, rather than exploring the rest of the available possibilities. Pyramiding, sometimes called 1-2-4-all, is a process where everyone in the group is given time to brainstorm individually before comparing ideas with other people. This means that we have the widest possible range of ideas, which we then choose to converge on.

- The process starts with an individual brainstorm (a few minutes is usually enough), before going into pairs and comparing ideas. If you want a smaller number of ideas at the end or just the best ideas, you could ask the pairs to pick their top five favourite ideas. In the next step, two pairs come together to form a 4 and between them they share ideas and select their collective favourite six ideas (as an example). Then this 4 can share their top six ideas with the rest of the group when it becomes time to present back.

- Rounds:

- A round (or go-around) is a tool when everyone in the group is asked to give their thoughts or reaction to something, going one after another in a seated or online arrangement e.g. clockwise around a circle. This is a great tool in making sure that everyone in the group has an equal opportunity to speak and should be used often. It can also be used by the facilitator when they are not sure how to proceed and would like support from the group, for example if there is a controversial proposal. An example might be: “Okay everyone so Linda raised a good objection and I’m not sure how to integrate that into our current proposal. Can I ask everyone to have a round so we can try to think of ways we could make this work?”

- Popcorn:

- If you don’t want to do a round or you think that not everyone needs to contribute at a certain stage, you can ask people to do it “Popcorn-style”. This just means people speak when they are ready to contribute, in no particular order of seating. The idea is that it’s like popcorn popping in a microwave without any direction or pattern!

- Prioritisation/voting

- Reflect back

- Energisers

Building a Culture of Trust & Support

A study by Google found that building psychological safety is really important for effective and healthy teams. What is psychological safety? It’s the shared belief that teammates have that they can throw out ideas without fear of judgement, they can take interpersonal risks and know they will not be rejected or embarrassed for speaking up, it’s a feeling of being comfortable enough to be yourself - your full self. So although the context of a professional working environment such as Google, is quite different from that of community organising, this sounds like a feeling we want to create in our teams. One of the researchers on the project said ‘If only one person or a small group spoke all the time, the collective intelligence declined.’’ (more here).

Here are the key aspects of building psychological safety according to Google’s study. Just remember: CACCOW

C: Celebration - Recognise people and their efforts. Make your teammates feel valued and make the work fun.

A: Autonomy: Allow people to do work as they see fit. Generally, if someone is doing the work, e.g., designing and printing the flyer, they should be the one who gets to have decision making power over it.

C: Caring: Don’t just meet for work, invest in personal relationships!

C: Clarity: How do we decide and do we know who’s doing what? The sections on decision making and group agreements are really relevant here.

W: Wholeness - Encourage people to bring their full selves and role model this through vulnerability. People generally don’t open up unless you open up to them, so be brave and share a personal story.

Resources on Building Psychological Safety

- Re:work Guide: Understand team effectiveness

- What Google Learned From Its Quest to Build the Perfect Team

Relevant Reading

- The Tyranny of Structureless

- Act Build Change

- Leadership, Organising and Action

- Group Agreements

- Sample Group Agreements

- 11 Practical Steps Towards Healthy Power Dynamics at Work

- How to foster psychological safety in your team

- Where’s the Psychological Safety for Speaking Truth to Power in Self-Organisation?

- Reinventing Organisations (video)

- Consensus, consent, advice, mandate

- Formal consensus

- 1, 2, 4, all

- Processing tensions

- Fierce Vulnerability Agreements

- Sociocracy for All

- Feedback without Criticism

How to deal with conflict in your groups

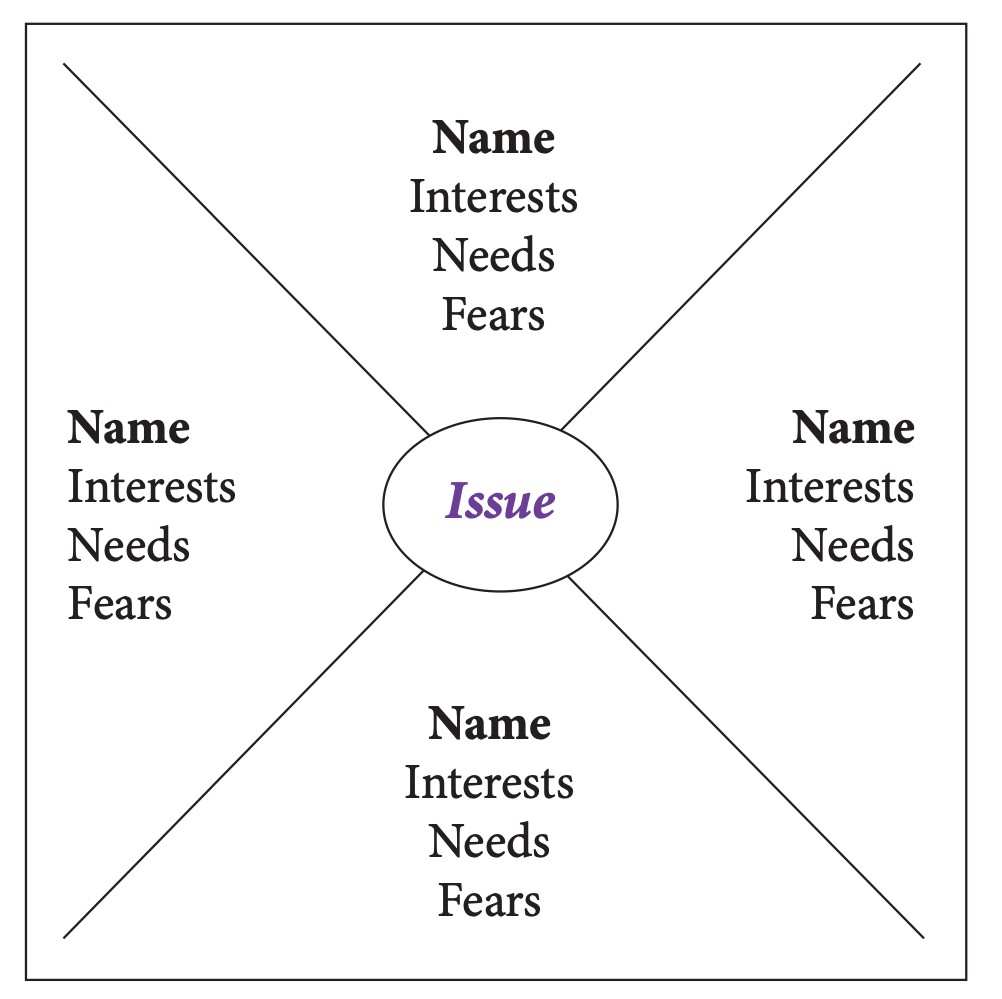

Every group and relationship experiences conflict, regardless of whether we are trying to bring about a revolution or play dominoes on the street. It’s simply part of being human, it’s also a particular feature of living in a world which is more mobile. Humans used to live in largely homogeneous groups, whereas today many different world-views and cultures are present in our communities.

So, it’s no surprise that so many of us struggle to collaborate with each other and then have difficulties finding a healthy way through conflict. Conflict is bound to happen while we unlearn old habits and develop new skills and awareness to work cooperatively and challenge oppression.

This guide is aimed at people and groups working for social change who want to develop an understanding of conflict and how to deal with it. There are sections on what conflict is, the benefits of addressing it, and tools to work through conflict and maintain healthy and effective social change groups.

What is conflict?

Conflict often be signalling:

- That some needs are unmet

- The power and/or trust to care for all the needs involved is not currently within reach

- Change is emerging

- Our relationships, agreements, understanding of what we are trying to do, ways of sharing power, and social systems, may need to evolve.

Conflicts are often painful, distressing, frustrating and destructive. Our personal, social and historical experiences of it are usually negative and traumatic. And so, we want to find a better way of navigating tension, conflict and disagreement because how we respond to it shapes whether conflict will tear us apart, or change, evolve and strengthen us.

5 Stages of Conflict:

1 - Discomfort

A little niggle that tells you a conflict might be brewing.

2 - Incident

A minor clue that acts as evidence of the growing conflict.

3 - Misunderstanding

The situation has escalated to a degree that one or both parties have developed false assumptions about the other.

4 - Tension

The clues here are much more obvious. This could be an argument, an emotional outburst, or out-of-character behaviour.

5 - Crisis

Breaking point for the relationship. By this stage all communication will focus on the conflict.

Why deal with it?

Conflict isn’t a problem - it’s an opportunity

Conflict can help us grow - in ourselves, in our relationships with others and in how we work together, in our groups and systems, and in getting clearer on the purpose that we share. We see a lot of conflict as offering an opportunity to evolve and build our collective power.

Understanding our conflicts and working through them can be a deeply empowering process for everyone involved. It can be hugely energising to find a way to connect with people you have a conflict with, and find a way through the conflict that everyone can live with instead of pretending it’s not there. Imagine you’re part of a group where people communicate honestly with each other, where everyone knows their own feelings, where there is a sincere desire to understand differences between people in the group, and to find solutions that are genuinely satisfactory for everyone.

Groups with a healthy approach to conflict will be better prepared to go the long haul together, and are better able to effectively bring about social change. Clear communication and trust for each other enable groups to make better decisions which takes into account more points of view. It also saves the time and energy that is sometimes spent on avoiding conflict.

Methods of Handling Conflict

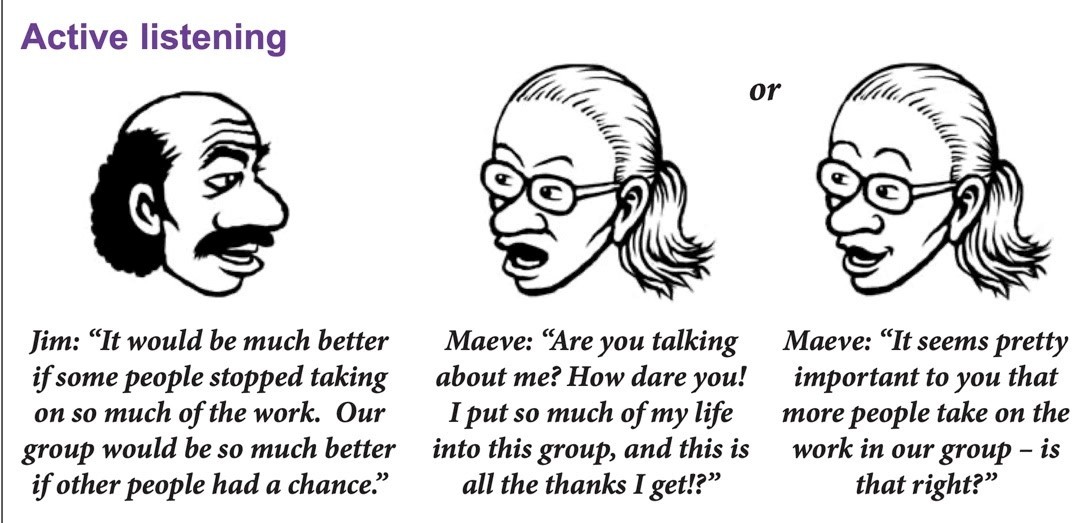

Good communication

In this section, we’ll explore what we can do to minimise conflict with others and deal with it effectively before it escalates. We will be looking at tools and skills to improve communication that will help to de-escalate a conflict.