Constitution resources

Resources and guidance referenced by the XR UK Constitution

- Integrative Election Process for Roles in XR UK

- Considered Majority Vote for Roles in XR UK

- The Advice Process

- Objection testing

- Decision Making Processes

Integrative Election Process for Roles in XR UK

[Note: this guidance is referred to by the XR UK Constitution (Section C.5).]

1. Discuss the role

The facilitator makes space for questions. Explain the purpose, domains and accountabilities where necessary. This may include, for example, what led to the creation of the role, and the key relationships with other roles and circles.

Make sure that everyone is clear on

- what this role is responsible for,

- how much time and energy it will take, and

- what the value of the role is in relation to the circle.

Set a term for the appointment. For Internal and External Coordinator appointments, the maximum term is six months. Otherwise, the term is typically three, six or twelve months.

2. Gauge interest from people

Who has capacity for the role? Whose passions might it engage?

If it appears that there may be only one candidate for the role, slow down and triple check that nobody else is interested. You might say something like "If we could offer any kind of support, what support might you need to take on a role like this?"

Make sure to encourage people who may not be confident enough to consider the role by listening first to those not already in the role - this gives your circle a chance to reflect on the importance of rotating role-holders and allowing people to experience different responsibilities.

For people on the edge of interest or who might love to do the role but don't have capacity you could say "what support might you need to take on this role?”.

For people who don't consider themselves available or suitable for the role, but who could be effective in it, might they take confidence from the support of others and the clearing of any blockages?

3. Make nominations

There are two rounds of nominations.

You can nominate yourself or anyone in your team.

- In person: write a nomination on a piece of paper and pass it to the facilitator who will read them out.

- Online: each person puts a name in the chat and sends at the same time for everyone to see. The facilitator may set up the process — “Type the name in the chat box, but don’t hit Enter. Anyone need more time? No, Ok. Then hit Enter on my count. 3…2…1…Enter”

-

In the first round each person gives a reason for their nomination (for example, "I nominated this rebel because they have good relationships with the people they'll need to work with, and a strong grasp of the strategy as it has evolved"). No one may abstain or nominate multiple people for the same role in the first round.

-

In the second round each person makes a nomination again, having heard and reflected on each other's explanations (it’s ok to stick with your first choice). No one may abstain in the second round, but nominations for multiple people may be permitted, if this has emerged in discussion of the first round. If anyone has changed their mind, they should give a reason for their new nomination.

The intent of this process is to share reasoning, but people may decline to justify their nominations if they feel strongly. They may not comment on anyone else's nominations.

4. Make a proposal and check for consent

Guided by the number of nominations, together with the reasons given for them and the needs of the role (from Step 1), the facilitator makes a proposal for who to appoint.

If appropriate, the proposal may include sharing the role between more than one appointee.

The facilitator then establishes whether everyone consents to the proposal. This includes the appointee(s), who should be asked last.

Seeking consent may sometimes be straightforward if there is a high degree of consensus.

If it is more contentious, then reviewing and refining the proposal should follow the Integrative Decision Making process. It may be that the proposal has to be modified to integrate any objections.

Once there are no objections to the proposed appointment,

- celebrate the appointment, welcome and support the new appointee(s)

- allocate an action point, usually to the Group Admin, to update shared records of the appointment (usually on the XR UK Hub).

Considered Majority Vote for Roles in XR UK

[Note: this guidance is referred to by the XR UK Constitution (Section C.5).]

The steps in the process are:-

-

The facilitator reads out the mandate of the role.

-

The term of the appointment is agreed by the team (normally 3 or 6 months).

-

Anyone willing to stand for the role comes forward or someone else does on their behalf. Nominations can also be made for people who have not put themselves forward, but who others in the team feel might fit the post well. If nominating someone in this way be careful not to put social pressure on anyone to stand if they are unsure [Note 1].

-

If possible each candidate has someone speak on their behalf [Note 2]. They explain the positive reasons why their suggested candidate would fit the role well (without commenting on other candidates). If there is no one to speak on behalf of a candidate, they can speak for themselves.

-

There is a round of clarifying questions for the candidates. These questions can also be responded to by the candidate or others in the team.

-

A vote is taken. All voting members vote using a secret ballot (private messaging the facilitator if using zoom.)

-

Everyone is asked if they have any objection to the candidate with the most votes being elected. Objections must be valid under the Constitution. Objections are tested using the Integrative Decision Making objection criteria in the XR UK Constitution section 7 f vi.

-

If there are valid objections, the facilitator works with the objector and candidate to integrate the objection. This means looking for a solution which removes the objection but which is also acceptable to the candidate. If an objection cannot be integrated a new election is held without including the candidate objected to. The facilitator decides whether this happens in the same meeting or a future meeting.

If there are no objections or if all objections have been integrated, the candidate is elected.

Note 1

If you put someone forward for a role without discussing it with them previously, and the first they hear of it is in front of a group, the social pressure (especially in large circles) can be very strong (even if meant in a kind way). It could push someone into a role for which they are not ready or emotionally in the right place. Encouraging someone to step into leadership can be a positive thing, but it’s recommended that you discuss the idea with the person before the meeting, giving them enough time to consider whether it’s right for them.

Note 2

Candidates speaking for themselves can lead to “campaign speeches” which is a group dynamic we would like to avoid in XR where possible. Having someone else speak for the candidate can mitigate this to a great degree and brings the speaker’s perspective and endorsement as well. This is why wherever possible we recommend the candidates have someone speak on their behalf.

The Advice Process

[Note: this guidance is referred to by the XR UK Constitution (Section C.7).]

The Advice Process can be practised in many ways, but they share a common factor, which is that anyone can make any decision within the mandate of their role after seeking advice from

- other roles who will be meaningfully affected, and

- people with expertise in the matter.

There are two key principles:

-

Advice received must be taken into consideration. The point is not to create a watered-down compromise that accommodates everybody’s wishes. It is about accessing collective wisdom in pursuit of a sound decision. With all the advice and perspectives the decision-maker has received, they choose what they believe to be the best course of action.

-

Advice is simply advice. No one, whatever their role, can tell a decision-maker what to decide. Usually, the decision-maker is the person in the role with a mandate that relates to the decision, or the person who either first noticed the issue or is most affected by it.

In practice, this process proves remarkably effective. It allows anybody to seize the initiative. Power is no longer a zero-sum game. Everyone is powerful via the advice process.

It's not consensus

We often imagine decisions can be made in only two ways: either by a person with authority (someone calls the shots; some people might be frustrated; but at least things get done), or by unanimous agreement (everyone gets a say, but it can be frustratingly slow).

It is a misunderstanding that self-management decisions are made by getting everyone to agree, or even involving everyone in the decision. The advice-seeker should take all relevant advice into consideration, but can still make the decision.

Consensus may sound appealing, but it's not always most effective to give everybody veto power, which effectively leads to 'minority rule'. In the advice process, power and responsibility rest with the mandate to make the decision. Ergo, there is no power to block.

Ownership of the issue stays clearly with the mandate-holder. Convinced she made the best possible decision, she can see things through with enthusiasm, and she can accept responsibility for any mistakes.

The advice process, then, transcends both top-down and consensus-based decision making.

Benefits of the advice process

The advice process allows self-management to flourish. Dennis Bakke, who introduced the practice at the American power-generation company AES (and who wrote two books about it), highlights some important benefits: creating community, humility, learning, better decisions, and fun.

- Community: it draws people whose advice is sought into the question at hand. They learn about the issue. The sharing of information reinforces the feeling of community. The person whose advice is sought feels honoured and needed.

- Humility: asking for advice is an act of humility, which is one of the most important characteristics of a fun workplace. The act alone says, "I need you“. The decision-maker and the adviser are pushed into a closer relationship. This makes it nearly impossible for the decision-maker to ignore the advice.

- Learning: making decisions is on-the-job education. Advice comes from people who have an understanding of the situation and care about the outcome. No other form of education or training can match this real-time experience.

- Better decisions: chances of reaching the best decision are greater than under conventional top-down approaches. The decision-maker has the advantage of being closer to the issue and has to live with responsibility for the consequences of the decision. Advice provides diverse input, uncovering important issues and new perspectives.

- Fun: the process is fun for the decision-maker, because it mirrors the joy found in playing team sports. The advice process stimulates initiative and creativity, which are enhanced by the wisdom from knowledgeable people elsewhere in the organiaation.

Steps in the advice process

There are a number of steps in the advice process:

- Someone notices a problem or opportunity and takes the initiative, or alerts someone better placed to do so.

- Prior to a proposal, the decision-maker may seek input to sound out perspectives before proposing action.

- The initiator makes a proposal and seeks advice from those affected or those with expertise.

- Taking this advice into account, the decision-maker decides on an action and informs those who have given advice.

Forms the advice process can take

Because the advice process involves taking advice from those affected by a decision, it naturally follows that the bigger the decision, the wider the net needs to be cast.

For minor decisions, there may be no need to seek advice. For larger decisions, advice can come through various channels, including one-to-one conversations, meetings, or online communication.

Some organisations have specific types of meeting to support the advice process, or follow formal methods. The Integrative Decision Making process, which XR UK uses for governance decisions, can be seen as a formal variety of advice process. Some organisations choose to have circles made up of representative colleagues who go through the advice process on behalf of the whole organisation.

When decisions affect large numbers, or people who cannot meet physically, the process can be held online.

- The mandate-holder can post a proposal on the UK Forums and call for comments and then process the advice they receive.

- The team can use decision-making software like Loomio, a free and open-source tool, or Murmur, which embodies Integrative Decision Making. The process for using the advice process on Loomio: start a discussion to frame the topic and gather input, host a proposal so everyone affected by the issue can voice their position, and then the final decision-maker specifies the outcome (automatically notifying the whole group).

Equal Experts, a UK network of software consultants, specialising in agile delivery, has written an open playbook to share their ongoing experience of a real-world implementation of the Advice Process (the organisation had approximately 1100 members in 2021).

Underlying mindsets and training

The advice process is a tool that helps decision-making via collective intelligence. Much depends on the spirit in which people approach it. When the advice process is introduced, it might be worthwhile to train colleagues not only in the mechanics but also in the mindset underlying effective use.

The advice process can proceed in several ways, depending on the mindset people bring to it:

- The initiator can approach it authoritatively ("I don't care about what others have said" or, alternatively, "I fully comply with what others - someone highly respected, or the majority - have said").

- They can approach from a perspective of negotiation or compromise ("I'll do some of what they say so they're happy, but it will increment my frustration levels by 1").

- They can approach it co-creatively, which is the spirit of the advice process ("I will listen to others, understand the real need in what they say, and think creatively about an elegant solution").

Role modelling

Coordinator roles in teams need to be role-models. Successfully distributing authority requires careful, proactive effort. Roles and mandates support this, but Internal and External Coordinators can help further by modelling and demonstrating the advice process in their own decisions. Other team members will take cues from their behaviour.

Modelling and demonstrating can take several forms:

- When you want to make a decision, pause and ask: Am I the best person for this decision? (That is, does it fall principally within my mandate? Might it also affect others' mandates? Am I most closely linked to the decision, or the person with most energy, skill, and experience to make it?). If not, ask the role you think is better placed to take the initiative. If they don't want to, you might be best placed after all.

- If you are the right person to make a decision, identify those from whom you should seek advice. Approach them and explain what you are doing. ("I'm using the advice process. Here is an opportunity I see. This is the decision I propose to take. Can you give me your advice?"). You can also share who else you are asking for advice. Once you've received advice and made your decision, inform those you consulted (and anyone else who should know).

- When colleagues ask you to make a decision ("What should I do?"), instead ask them "What is your proposal?". Share your advice and suggest who else to ask. Remind them the decision is theirs.

For many of us, unlearning the habit of making all the decisions is hard. It requires commitment and mindfulness. If you find yourself falling into the old pattern, take the opportunity to acknowledge your mistake, and restate the importance of the process. This can turn a mistake into a powerful learning moment. Better habits are formed through repeated practice.

[Note: this text is largely copied, with light adaptation, from a longer one that is part of the Reinventing Organizations Wiki. Copyright belongs to the original creators of that text. [Note: Once we have got more of our resources in order, David as SOS Resource Steward will contact Frederic Laloux to check this is OK. He has been a friend to XR in the past.]]

Objection testing

[Note: this guidance is referred to by the XR UK Constitution (Section C.7).]

When a proposal is brought using the Integrative Decision Making process, the facilitator asks each member of the team if they have any objection.

If there is an objection, the facilitator tests it by asking questions to determine whether it is valid within the terms of the Constitution.

Integrative Decision Making aims to integrate all valid objections to a proposal.

To be valid, an objection must meet all of the following criteria, which can be addressed in any order:-

| Criterion | Valid | Not valid |

|---|---|---|

| The proposal causes harm - where harm is defined as degrading the ability of the circle to achieve its mandate | Is your concern a reason the proposal causes harm? or… | … Is your concern that the proposal is unneeded or incomplete? |

| The proposal limits the objector from achieving the mandate of one of their roles | Would the proposal limit one of your roles? or… | … Are you trying to help another role or the circle in general? |

| The objection is created by the proposal and does not exist already | Is the harm created by this proposal? or… | … Is it already a concern, even if the proposal were dropped? |

| The objector is reasonably sure the harm will happen or doesn’t consider the proposal safe enough to try | Would the proposal necessarily cause the impact? or… | … Are you anticipating that this impact will occur? (If "Yes," ask the next question) |

| Could significant harm happen before we can adapt? or… | … Is it safe enough to try, knowing we can revisit it at any time? |

If the grounds for objection are that the proposal goes against a policy of the circle or its broader circles, or breaks a rule in the Constitution, or clearly violates XR’s Principles and Values or Volunteer Agreement then the objection is automatically valid.

Facilitating Integration

- It is up to the proposer to see if they can find a way of integrating a valid objection.

- They can ask the objector for help with this: “What can be added or changed to remove that issue?”

- Or ask for contributions from anyone to resolve the issue.

- With each suggestion, the question for the objector is “Would this resolve your objection?”, and the question for the proposer is “Would this still address your tension?”

[Note: Parts of this text are derived and adapted from the Governance Meeting Process published by HolacracyOne with permission, © HolacracyOne, LLC.]

Decision Making Processes

[Note: this guidance is referred to by the XR UK Constitution (Section C.7).]

This page includes some basic steps and then details specific decision making processes. It is aimed mainly at facilitators and is derived from the earlier Guide to Decision Making on the Streets.

A fair process helps to get people on board with a decision that may not be their first choice. If people feel what they care about has been heard and the decision is made for a legitimate reason, they are more likely to accept it and remain engaged with the group. Finding a way to balance a fair process with an efficient one is the fine arts of facilitation!

Consent Based Decision Making

The overarching approach we recommend taking to decision making is consent based decision making. Consent based decision making is about finding an option that sits within everyone’s range of tolerance (“OK, I can live with it”), not their range of preference (“I love it”). This is because finding a proposal that everyone loves will be really difficult while finding one that everyone can live with will be a lot easier. Let’s go with a proposal that’s good enough, rather than trying to perfect it. Explain this approach to the group before starting the decision making process.

Tips for before starting the process

It’s good to be clear about the type of decision making process that will be used before the process starts. This way people will set their expectations, for example, whether they will have to accept what the majority wants to do or whether the proposal will be changed based on their concerns. Always state the decision making process and give a brief explanation before starting it. Don't get into endless discussions about what process to use, you should decide how to decide as their competent and confident facilitator.

Most decisions are time-bound, especially during rebellions, so decisions have time limits. Getting clear on the time limit before the meeting and stating it at the start will help the group understand why you’re using a specific decision making process, e.g., “the police will make arrests within 5 minutes, so we’re going to do a majority vote”.

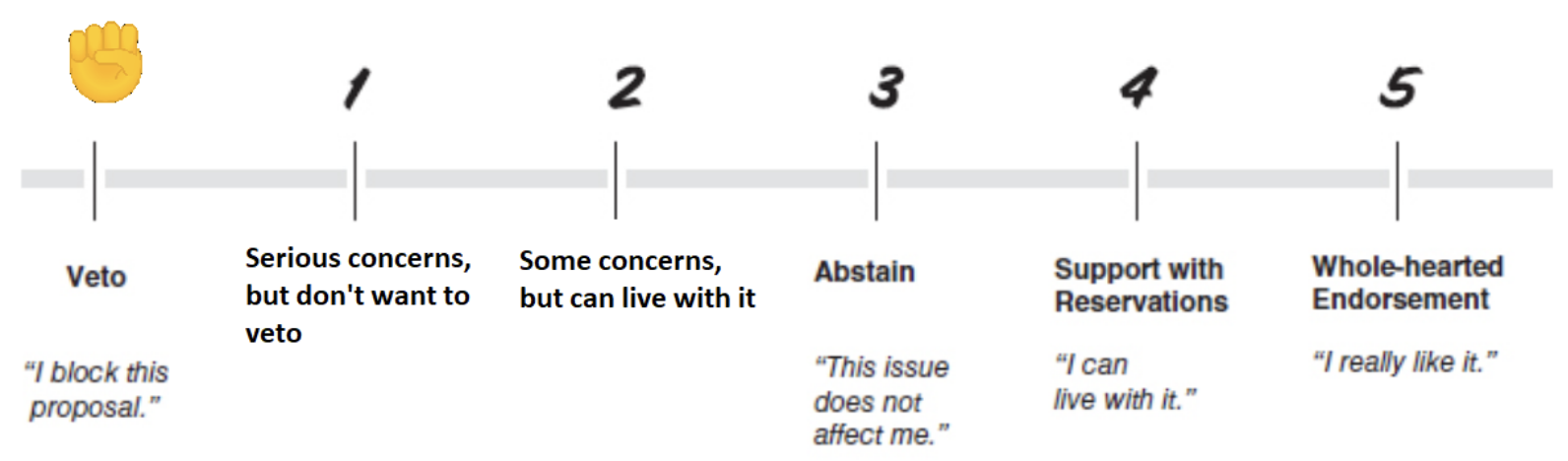

1. Fist to Five

Fist to Five is a decision making process which allows people to state more than yes or no. This is very similar to consent except that people can give more nuanced responses. It’s important to people to be able to express dislike, so we need to give them a way of doing it that's not a block. They can state any of the following options:

Follow the steps for either a meeting or people’s assembly as described above, then:

Follow the steps for either a meeting or people’s assembly as described above, then:

(Explain the instructions very slowly, maybe even twice. Don’t be rushed yourself or people will feel rushed and they don’t like it.)

- Explain the different response options, i.e., the Fist to Five are (“Instead of asking you to vote yes or no, I want you to hold up a number of fingers:

- 5 finger if you really like the proposal

- 4 if you think it’s pretty good

- 3 if you want to abstain (e.g., “I’m indifferent”)

- 2 if you have reservations but can live with it going ahead in order to not hold up the group

- 1 if you have serious concerns, but wouldn’t veto this version of the proposal (see below)

- Fist if you have a major concern that means you want to veto this version of the proposal. It’s very important to make this clear to the group. Vetoing the proposal should be grounded in a reason ( e.g., violating XR UK’s Principles & Values or someone may get hurt due to the proposal), rather than personal preference (e.g., “I just don’t like it”).

- State the threshold at which the proposal will be passed, e.g., “Given that we have 10 more minutes so need to make a decision quickly, the proposal will pass unless someone blocks”. (This sets the threshold for passing the proposal as quite low, so it is quite likely to pass.)

- If there is a veto or serious concern, you can either ask the person voicing it what they would need to amend to pass the proposal.

- Ask the proposal/idea/question and record the number of people for each number. Hopefully, major concerns will have been voiced before this stage, but just before asking people to respond remind them that you do want to hear major concerns if anyone has any because then we can amend the proposal to make it better.

- Alternative option: for a secret ballot you could choose to ask people to close their eyes if they’re comfortable doing so.

- It's useful to check in if you have large quantities of low numbers - if there isn't a block, but everyone is at 1 finger (they have concerns), then you might want to spend more time thinking about this proposal - if you have time. You could say something like "I'm seeing lots of 1s - can I invite one or two people to speak to why they've given this a 1?" Then use that to decide if we need to resolve something before moving forward.

- State the outcome:

- If there is no block (i.e., a fist) and you’re short on time, consider the proposal passed.

- If there’s a block, invite that objector(s) to share their reasons, then work with them and the proposer to amend the proposal and ask people to decide on the new version by showing a number again.

- If you have time, invite those who have expressed serious concerns (1) to share their concerns. If multiple people have serious concerns, it’s worth considering whether to work with the proposer and objector to amend the proposal if possible, as described above.

Pros: Allows for more nuance; people can express that they have a concern but don’t want to block the proposal. Asking for a number can speed things up.

Cons: Need to explain what the numbers mean and people need to remember it so it can be too complicated in time pressured situations. You need to start off with one proposal; this will not work when there are several on the table. Works best with a small group of people, say less than 10.

Thresholds: As the facilitator you can set the threshold; you can declare the decision as passed even if there’s one or two people disagreeing (majority vote situation) or decide to hear from everyone who has a niggling concern. The threshold you choose will depend largely on the time limit and the seriousness of the decision. If people do not agree with the threshold, they will tell you. As a facilitator, it's most important here to keep open and to welcome refinements - not always easy, especially when under pressure.

In the above example, we’ve set the threshold in favour of the proposal passing since it will only be blocked if someone concerns so serious they are prepared to veto the proposal. This is deliberate - we want to be biased in favour of taking action and trying things.

However, we also want good proposals, so if you have the time or the decision is very important, consider resolving the issues of those who have serious concerns - the facilitator and group can set the threshold wherever they like.

2. Majority Vote

The group is expected to go with what the majority is in favour of.

Follow the steps for either a meeting or people’s assembly as described above, then:

- Ask the group to raise their hands if they are in favour of the proposal, against it or abstaining (eyes closed for a secret ballot).

- Record the number voting for each.

- Announce the decision.

Pros: Fast, perfectly fine to use it when a decision needs to be made super rapidly or is inconsequential, e.g., “shall we move to the shade?”. But when the decision will be contentious, Fist to Five would be better. Works well when there are many people. It’s OK to disagree and this method reflects that.

Cons: The minority may be unhappy, feel undervalued and disengage from the group.

3. Temperature Checks

Temperature checks can be seen as a type of voting, but they are usually not taken as a formal decision unless all hands are in the air or the decision is inconsequential (e.g., should we stay here or move to the shade?”)

Follow the steps for either a meeting or people’s assembly as described above, then:

- Tell people you’re going to do a temperature check and what the response options are: People do jazz hands in the air for yes, and downward jazz hands for no.

- Ask the question.

- Announce the decision.

Pros: gives a quick idea of how the group feels about something.

Cons: can be ambiguous what it means when people put their hands in the middle, can be hard to look at a crowd and determine how many people are doing each, can be hard to see hands that are down because of people standing in the way.

By asking yes or no (or any question with a binary response), you cut down on the amount of discussion needed. Thinking about the different issues related to the topic and asking a series of binary questions can be useful to get a sense of how the group feels really quickly. It can also be useful to check in with one or two people who indicated that they disagreed so that at least they can feel heard and hopefully be less frustrated.

Comparison between the processes

Below is a table allowing comparison of three different decision-making processes, Fist to Five, temperature check, and majority voting. The table outlines their details and relative speed to aid you in choosing the right process for a given decision making scenario.

| Fist to Five | Majority Voting | Temperature Check | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of response options | 6 (see section above) | 3 (yes, no, abstain) | 4 (Agree, not sure, disagree, abstain) |

| Speed | Medium | Faster | Fast |

| Strength | Allows people to give more nuanced responses & allows proposals to be adjusted into something everyone can live with, rather than just rejected | Quick & can be used when there are several options available | Quick & can be used when there are several options available |

| Weakness | Slightly more complicated so will take more time to explain | Many people may be frustrated | Can be ambiguous what hands that are at chest height mean |

How do I know what process to use?

There are many different aspects of the decision that may influence which process you want to use. The key ones are:

- Is the decision urgent? We’ve provided some fast versions above, but you will have to use your intuition to decide what’s the best way to balance discussion and speed.

- Is the set of options clear? See below on brainstorming if there’s no options. If there’s several you could do a majority vote to choose the most popular option and then do consent decision making to ensure it’s something everyone can live with.

- How contentious is the topic? Are there a lot of feelings? Best to discuss it thoroughly. As stated above, people usually accept a decision when they feel what they care about has been heard and the process is fair, so it’s worth slowing things down and hearing from people when tensions are running high. A round of hearing from everyone is always a good idea in tricky situations, make sure it stays as a round though and doesn’t become a discussion.

- How consequential is it? For example, are we considering moving to the shade to hold the People’s Assembly or deciding on an action that will trap MPS in their offices for days? This greatly determines the decision making process you’ll want to use. Moving to the shade can be decided by a vote or temperature check and no one will be that upset. A very spicy action will need strong agreement with lots of time to hear dissent and seek advice and feedback from those with expertise.

- Does it affect a large number of people? If yes, have you gotten their input? This is tricky because high profile, spicy actions in some ways affect everyone in the movement. We recommend reminding people that the Principles & Values and the Rebel Agreement are what we have to guide behaviour and that people have the autonomy to make their own decisions within those parameters.

- Who’s best equipped to make the decision? If there’s a person or a small group with the information and knowledge to make the decision and you trust them, why not let them make the decision? The group could share some thoughts with them and then leave them to it. Remind people that sometimes it’s OK that some people have their say and others don’t, because it might be an issue that person cares about in particular while everyone else doesn’t care (e.g., a focus on health and safety, or a focus on fairness).

- Can it be trialled for a period of time? Or is it a one off event? If it can be trialled, ask those with concerns to give it a go with the knowledge it can be changed in a day or two if they still have concerns.

- Ask if anyone has a suggestion (and ask them to be brief) and ask the group to use wavy hands to signal what ideas they like. Capture them all somewhere so everyone can see if possible. Do a decision making process above on the idea that got the most wavy hands. Best to set a time limit on this.

- People’s Assemblies are great for generating many different ideas because people have the chance to discuss in small groups and may be more comfortable sharing wacky ideas. Again, watch the group to see what ideas get the most wavy hands and pick that one.

- Negative Brainstorm: pose the question in the opposite form, e.g., what action do we not want to do today? This will take some time.

- Even though you’re the facilitator, don’t be afraid to suggest one if you have one.

What if there are several options?

Are the options mutually exclusive? Could the options be combined? Remember, you may not need the perfect option, but an option that is good enough. If all your options are good enough then see what elements of them could be combined, but it is possibly more important to simply start taking action on one of them. In this situation, if you are stretched thinly, maybe the key criteria is which option will take the least of your limited capacity, or which can be delegated to a volunteer or temporary team.

Keeping track of the different options is essential, but can be difficult, especially when there’s many different variations of the same option. Visual aids can help such as writing it down and labelling them plan A, etc. Although if you refer to it as “Plan A” make sure you’re all on the same page about the plan you’re talking about. Then get people to vote so that you can narrow down the options and explore the top 2 further. Also, consider 'unpacking' exactly what people mean by specific words.

Try asking people to vote for each proposal and use consent based decision making to make sure it’s workable for everyone in the group.

Keeping it Smooth

A good facilitator can help keep the group on track to making a decision that works for everyone in the group. Encourage people to come to the meeting with all the information they need to make a decision. Point out logical fallacies (e.g., “those options are mutually exclusive”) and correct information when you notice it.

Information: Rebellions can be hot beds for rumours. Tensions can run high, people can be on edge which leads to exaggeration, especially when information is being relayed through multiple people. For example, the police changing shift can lead people to jump to conclusions that they are trying to clear the site. Fact check information and don’t share it unless it is from someone you trust personally or you’ve witnessed it directly. As a facilitator, remind the group to make decisions based on the best evidence available rather than hearsay.

Dissent: It’s your job as facilitator to ensure that everyone in the group can share their thoughts, especially the voice of doubt or concern that will probably make the proposal more robust. You can decide to set the threshold for dissent really high (“Does anyone have any major concerns with this proposal?”) or really low (“Does anyone have any little grumblings with this proposal?”). If there are people who you think might have a hard time speaking up, you can set the threshold lower for them. You may also model some dissent yourself so people feel comfortable saying theirs.

External factors make the decision for you: Make sure that the decision being discussed is not already decided by an external factor. For example, during one people’s assembly in the rebellion last October people spent a long time deciding whether to hold a road overnight or not. Half way through the People’s Assembly, someone asked “Who here is actually willing to sleep in the road tonight?” Two people put up their hands, and so the decision was pointless because there were not enough people willing to do the proposed option.

The key thing here is that if there is work to be done, check that enough people are willing to do it and they are heard on the issue. This should be done during the fact finding stage before you start the decision making process.

Other external factors could be that if we don’t act this minute, the police make the decision for you, so that limits you to choosing options already on the table.

Polar collaboration: Ask those who feel strongly about the issue to work together outside of the meeting and come back to the group with something that works for them. This is useful when there’s a few that care and others that don’t and it saves the latter sitting through those who care thrashing out the details.

Discouraging unnecessary permission seeking: Sometimes people bring a decision to the group that they can actually make themselves because it’s in their role description/mandate. Check whether the decision needs to be made by the group or whether that person can make the decision by themselves - they may still want to hear advice from the group. You don't have to know the mandates, exactly but use your judgement and if in doubt, just ask "Are you sure you need a group decision/input on this? Is it a decision you can make within your mandate?"

Amplify: When someone from a traditionally marginalised background makes a contribution it can often be overlooked or repeated by someone else who takes the credit. Accrediting the originator of the idea with their idea can be really helpful to make sure the idea nor the person doesn’t get overlooked. Some facilitators highlight that they are not being strictly fair when it comes to young people for example. They take their points/questions more often and give them more time to speak, and publicly acknowledge that I am doing it and why...

Facilitation leadership: Facilitation leadership is helping the team achieve their purpose and ensuring everyone can contribute so the team can harness its collective wisdom. See more under Leadership in the Building Healthy Teams [link to come].

Consistency: Although it’s great to represent representatives and leaders, on the time scale of a rebellion, it can lead to a lack of consistency in who is turning up to meetings and so there’s no capacity to get to know each other and build trust. You could encourage the representatives that do come to site meetings to show up consistently.

Preparing to facilitate: As a facilitator, you need to bring groundedness, fairness, sensitivity to emotions, and wisdom. Yes, that’s a very tall order! If you are to facilitate, try to find some quiet time beforehand to relax a little, look after your needs and ground yourself so you can stay cool and collected and help others do it too.

Framing questions: the direction in which a proposal is made, e.g., "the proposal is that we leave the road" vs "the proposal is that we stay here", can influence the outcome of the decision. People tend to agree with questions and no one wants to be the naysayer (or at least it can be difficult to speak up sometimes), so people will probably tend towards passing the decision. That means you’re more likely to stay if the proposal is that we stay where you are, and more likely to go if the proposal is to stay put. There’s not much that can be done here because there’s no neutral framing in this example, but it’s something to be aware of.